Building infrastructure for growth

Executive brief

- Demand for skill-led higher learning is surging as countries, industries and professionals need to develop across their lifetime

- Education systems need mechanisms for spotlighting learning needs and incentivizing universities to provide relevant resources

- New skill-led higher learning indicators can stimulate and shape this emerging education economy and university growth

Decades of high-participation tertiary education have accelerated the global need for lifelong higher learning and development. Professionals need skilling throughout their careers, which is typically complex, nuanced and dynamic.

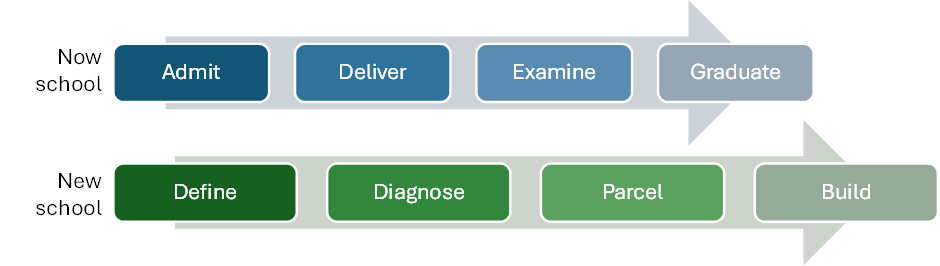

This sparks a need for skill-led learning which positions savvy learners at the forefront of agile university-led value-creation processes. Skill-led learning begins by defining desired capabilities, then diagnoses existing skills to engage learners in all and only the enriching education supports and challenges which they need to succeed. Learners realize rapid and relevant returns from parceled experiences, and over time stack up portable accomplishments into accredited tertiary and industry credentials.

Such education innovation hinges on incentivizing and shaping markets, and universities seizing opportunities to deliver learning to people across their lifespan. Frontier work has propelled this emerging education economy and university growth. This work stimulates the investment to spark new capabilities, partnerships and successes.

Hamish Coates and colleagues

Centering skill-led learning

In recent decades higher education has expanded substantially, opening opportunities for hundreds of millions more people to obtain degrees and engage in professional work. Expansion interests focused initially on expanding bachelor- then master-level qualifications for school leavers. In countries which built high-participation tertiary education systems since the 1990s, especially as school-leave cohorts decline there is pressing and widescale need to make higher education available to a much broader set of learners. Global expansion sparks a need for skill-led learning which positions learners at the forefront of an agile value-creation process. Skill-led learning begins by identifying desired learner or community capabilities, moves forward to diagnose existing skills, and then engages learners in all and only the enriching education supports and challenges which they need to succeed. Learners realize rapid and relevant returns, and build portable accomplishments into accredited tertiary and industry credentials. To be clear, this is not the ‘recognition of prior credentials’ but the ‘diagnosis of learning needs’. Curriculum is fluid not fixed. Learners are recognised for what they know and can do.

Figure 1: Now school to new school

This all sounds very useful. It is apparent, however, that advanced economies lack mechanisms for spotlighting learning needs and helping higher education institutions provide relevant programs and activities. Regulatory mechanisms even get in the way. This fuels a need for innovation. To this end, this briefing builds on Singapore-based research which sought to help universities grow and meet opportunities to deliver learning to people across their lifespan.

This work springs from a swelling array of frontier work. The ideas below build on formative research shaped by Singapore’s SkillsFuture. In China, Tsinghua University has merged continuous education and online education offices. Korea’s Academic Credit Bank System is pioneering new forms of recognizing diverse formal and non-formal learning experiences. In the United States, Stanford University is promulgating its Open Loop University model, Georgia Tech is building Lifetime Education, and researchers are clarifying the ‘sixty-year curriculum (60YC)’. Instead of people being sorted by capability into a small number of formal postsecondary qualifications before embarking on a lifetime of work, these initiatives signal people’s engagement in a career-long programs of learning and upskilling. Rather than providing formal foundations which are augmented through work and informal learning, education itself plays an ongoing role in co-creating innovation frontiers.

Momentum gathers pace

Demand for skill-led learning is buoyed by an accumulation of factors. Most broadly, higher education institutions have been subject to a swathe of policies seeking to promote workforce capability. In many countries, governments and industry groups have advanced omnibus and sector-specific initiatives to upskill reskill workforce capability. Demand has swelled from the larger number of people and institutions engaged in higher education. At the occupational level, economic advance also spurs an ongoing swing towards professional roles which require higher education. Universal participation rates in higher education over recent decades have led to high levels of degree attainment and stimulated larger demand for continuous reskilling. Such demand has been amplified as professionals work for longer and need career-long reskilling to service more mobile careers.

Higher education institutions have made substantial investments to serve this surging demand. Traditionally, ‘adult’ and ‘lifelong learning’ and ‘continuing education’ have been somewhat marginalized in universities, relegated to small units or those with no clear strategic role. This is changing swiftly. Universities have been investing in online and hybrid learning, alternative credentials, redesigned learning resources, and embracing an array of partnerships. Such initiatives have been constructed in response to the demand dynamics identified above, to tap into new sources of funding, and to counter new commercial competitors. Higher education institutions are maneuvering to become regionally or globally positioned, and expand their engagement with employers to improve students’ employability. While institution-, discipline- and profession-specific efforts are important, it is hard to ‘add up’ such initiatives in ways which help understand, design, incentivize and regulate these new markets. Indeed, unleashing a swarm of freemium or priced non-credit or credit-bearing online resources, even with ‘stacking potential’, badges or microcredits, is likely to multiply complexity and confusion, and hinder clarity and progress where it is needed most. Established university evaluations and regulations do little to articulate the emerging environment, and have in fact shifted attention away from skill-based learning into structured qualifications. Even and especially if the market for skill-led education is likely to be largely commercial and private in nature, there is a need to clarify what is going on, how institutions can contribute, and how to make it worthwhile for them to bother. Finding institutional and educational coherence is important for future growth and contribution.

Designing the skills-led higher learning economy

Many education systems have set up means to engage higher education institutions in lifelong learning to meet swelling community and industry demand. A common missing link, however, is a mechanism to incentivize higher education institutions to engage. New information is needed to define and stimulate the required investment.

This briefing reports research which designed a framework with indicators to propel higher education institutions to engage in skill-led learning. Ultimately, this comparison instrument is intended to make available information on the suitability and capacity of institutions to provide more varied forms of education to people across a much larger and diverse range of demographics. While designed and validated in Singapore, it was foreseen that the evaluation tool should be regional and even global in vision given growing worldwide interest in skill-led learning.

Table 1 presents the validated framework and indicators, reflecting the outcome of the two-year research project. Three dimensions were defined to help focus the indicators and direct attention and work by institutions and others:

- Capabilities: Whether higher education institutions have capabilities to promote and practice skill-led learning, and to provide access to all learners

- Partnerships: Forging collaborations with industries and the community to understand and provide for the diverse learning needs of skill-led learners and ensuring the relevance of such skills and knowledge, and

- Successes: Extent of various achievements in the provision of skill-led learning.

Table 1 lists questions for each indicator which are designed to be answered by a single representative at each institution. Reports furnish a metric of higher education institutions’ capabilities, partnerships and success in their provision of skill-led learning.

Table 1: Framework, dimensions, indicators and questions

| Dimensions | Indicators | Questions |

| Capabilities | Strategic Intent Reflecting an institution’s strategic direction vis-à-vis lifelong learning | Lifelong learning KPIs Strategic emphasis Leadership arrangements Lifelong learning budget |

| Flexible Learning Institution production of accessible and relevant courses for lifelong learning | Prior recognition and access Lifelong learning course flexibility | |

| Support for Learners Helping learners to engage | Academic support for learners Teacher professional development | |

| Partnerships | Promoting Learning Active promotion of opportunities to potential learners, industry and community | Lifelong learning promotion budget Importance of promoting lifelong learning Development of engaged lifelong learning programs |

| Developing Partners Extent to which institutions ‘reach out’ beyond campus | Courses co-developed with communities Courses co-developed with industry Courses delivered for industry partners Courses delivered for community partners Teachers who engage with industry | |

| Successes | Quality Quality of courses as reported by adult learners | Satisfaction of learners Application of learner knowledge/skills |

| Inclusivity The extent of difference in profile of learners engaged and graduated | Student diversity | |

| Outcome Evidence of impact of lifelong learning provisions | Graduation rate of adult learners Dropout rate of adult learners |

This infrastructure was tested with institutions in three countries, improvements made, in-depth validation with another 12 higher education institutions. This deep study revealed the need for ongoing discussion and support during data collection, not least to ensure that an ‘institution-wide perspective’ rather than ‘lifelong learning unit’ perspective was delivered.

Much was invested to establish these dimensions, indicators and questions. On face value they seem straightforward. Yet they reflect a delicate balance of the lifelong and higher education worlds which they attempt to unite, between global generalizability and institutional relevance, between ideas and technical or operational practicalities, and between research, policy and practice. The work revealed that higher education institutions have amassed data for external reporting purposes, which needs to be augmented and modified to reflect the nature and level of lifelong learning.

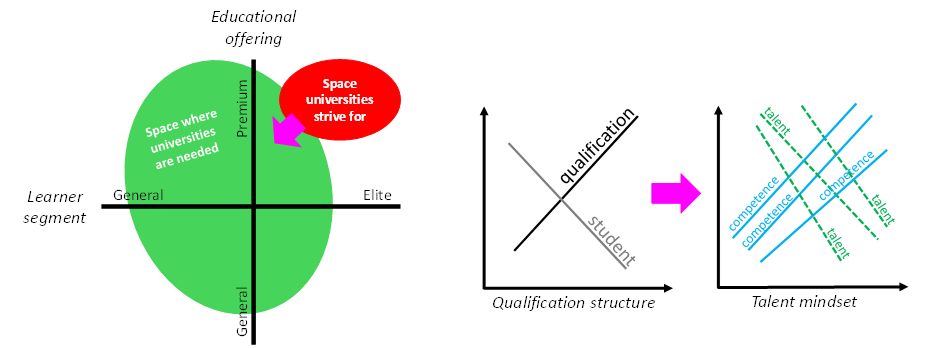

This infrastructure sparks a raft of far-reaching reforms which work to engage higher education institutions in skill-led learning. In short, while higher education institutions, primarily universities, have traditionally maneuvered to sell priced-up and bundled and prestige qualification products to premium learner segments, there is growing population-wide and career-long demand for more individualized and atomized forms of learning. Figure 2 depicts this misalignment problem in terms of institutional positioning and product offering. To align university provision with future demand, universities need to be steered away from homing in on affluent segments with premium products and offering bundled qualifications to individual students. As the arrows convey, it will be necessary to shift into less affluent market space and offer specific competencies that match and augment specific talent needs.

Figure 2: Addressing the misalignment problem

Clearly, transforming higher education for this new kind of economy requires widescale changes to all segments of the education value chain. This means redesigned institutions and ultimately markets.

Table 2 conveys the broad-ranging changes required, in which higher education institutions shift in demand-centric ways to actively identify and stimulate and reward formally recognized learning.

Table 2: Sparking the new higher education economy

| Dimension | Prevailing situation | Transformed agenda | Change characteristics |

| Vision | Progress world-class research | Advance the populations’ talent | Integrate lifelong learning and industry collaboration for workforce needs |

| Promotion | University and program information | About small parcels of learning | Transition to personalized learning pathways based on real-time demand |

| Product | Multi-year accredited qualifications | Atomized learning parcels | Shift towards modular, stackable learning units that can be tailored for diverse career pathways |

| Market | Premium individual students | Anyone with talent needs | Expand accessibility through industry-sponsored micro-credentials and digital inclusion initiatives |

| Accreditation | National regulatory mechanisms | National regulatory mechanisms | Align with global skills and integrate industry-validated credentials |

| Quality | Governmental and professional authorities | Trust network using multisource review | Introduce blockchain-based credential verification and peer-reviewed accreditation systems |

| Teachers | Regular academic faculty | Specialized education engineers | Employ a hybrid model integrating industry professionals, AI tutors, and education engineers |

| Assessment | Examinations and assignments | Authentic assessment tasks | Replace traditional exams with competency-based evaluations and real-world project assessments |

| Certification | Formal university transcript | Talent development certificate | Develop digital skill passports with real-time competency tracking and employer recognition |

| Timeframe | One to four years | Hours, days or weeks | Enable on-demand learning modules that support upskilling within changing job markets |

| Affiliation | Linked with university | Linked with learning pathway | Foster continuous learner-industry connections through professional networks and alumni engagement |

| Funding | Payment for qualification | Payment for learning parcel | Introduce subscription-based and employer-funded learning models to enhance accessibility |

| Admissions | Prior qualifications and experience | Capability and readiness to learn | Implement AI-driven aptitude tests and portfolio-based admissions for fairer access |

| Support | Responding to reported needs | Proactively identifying learner needs | Deploy predictive analytics to offer support and career-mapping tools |

| Advice | Product-oriented branding | Predicting individual potential and growth | Offer AI-personalized mentorship programs with adaptive learning recommendations |

| Rationale | Obtain formal credential | Augment vocational capability | Shift focus to lifelong skill-building with dynamic, evolving pathways |

| Focus | Framed by conventional disciplines | Shaped by industry and social problems | Promote interdisciplinary learning and applied problem-solving through real-world challenges |

| Location | Campus, online or blended | Campus, online, in community or blended | Enhance hybrid models with immersive VR/AR environments and workplace-integrated learning |

Universities stepping ahead

Success hinges on universities’ hunger and action. By seizing new revenue streams, adaptive learning models, industry partnerships, education reforms, and technology-driven skill validation, universities can shift towards learner-centric education that fosters continuous talent development, workforce resilience, and viability. This will position universities as continuous and relevant knowledge hubs, integral to workforce transformation.

Many universities have opened-up since the late 1990s with ample corporate scope to tap into veins of revenue. Universities need to maneuver beyond traditional education models by offering micro-credentials, stackable certificates, and subscription-based learning, opening up new income streams.

Among the tapestry of required innovation, new partnerships are required for this approach to talent development. Learners are most likely to be those people who would not otherwise participate in higher education. They may have a vocational background, have obtained a qualification years ago, or may have skipped tertiary education altogether. Along with learners, industries and professions play an important co-creation role, helping with learner identification, capability assessment, support, and recognition. Universities will need to partner with corporations and governments to co-develop programs that address workforce needs, ensuring funding opportunities and industry-backed credibility.

New education resources are required to drive skill-led learning. Nationally and professionally accredited courses are too heavy and rigid, though they provide important grounding and resources. Rather, such materials must be embraced and distributed in parcels relevant to each learner, with delivery mode is tuned to learner needs and learners deciding whether to participate in assessment to earn stackable credits.

Evidently, new platforms (digital and otherwise) are required to facilitate skill-led learning. Existing institutional structures and platforms support the delivery of pre-packaged supplier-defined courses. Smarter learning platforms are needed to diagnose existing capability, recommend learning goals and pathways, leverage AI to predict industry trends and align educational content accordingly, and coordinate modular and secure digital credentialing systems. Management platforms need to coordinate different student and course profiles. Ample marketing and support infrastructure is already primed to pounce. As always in education, the most important and difficult frontiers to push forward are those which are social, cultural, and professional. Career-spanning learning partnerships go beyond discrete qualifications, alumni relations and philanthropy, and transactional teaching experiences. Novel managements systems are required which give play to outcome-based learning metrics, social engagement, and education contribution.

Advancing skill-led higher learning

Of course, given full play such market and institutional changes are multifaceted and profound. Higher education systems and institutions across the world are being called to make more community and industry engaged contributions. Inducing higher education institutions to participate in skill-led learning has never been more urgent and important.

Further investment is needed to harness and advance this agenda. Further technical development of the inventory is needed, including consultation and statistical validation. There is the task of engaging universities in the broader and ongoing evaluation. The most profound and effective means for engaging universities in validation and ongoing data collection is of course to make the platform easy and useful. This goes beyond universities and also embraces active and potential learners, business and industry, government and other system-level actors, and international communities.

Once sidelined to a dusty building on the slow side of campus, this field has shifted into the core of education growth. Obviously, the field builds on evaluation and rankings, and on lifelong learning. It shines renewed institutional, policy and community light on the core socioeconomic implications of institution engagement in lifelong learning. It spotlights Asia-based education and skills policy innovation, and documents its potential for broad application across the large region and beyond. It contributes to broader public policy analysis about the changing role of higher education in the world. The briefing launched by identifying the need to build mechanisms which unite universities and the world of work in ways which help people engage in higher learning throughout their lives. All advanced economies with established professional workforces and developed higher education systems are confronting this need. This is currently a challenge given the limited policy and information infrastructure to guide individual and institutional engagement. As the research in this paper advances it seeks to turn such challenge into opportunity.

Further reading for inquiring minds

This briefing was written by Hamish Coates, with input from Johnny Sung, Yee Zher Sheng, Albert Liau, Aggie C Xinhui, Liu Liu, and Mary Barry. Contributors acknowledge precursor support from the Singapore Ministry of Education and Singapore SkillsFuture.

Beaton, J., Xi, G. & Coates, H. (2022). The digitalization of higher education: The transformative role of EdTech. In: Dee, J.R. & Leisyte, L. (Eds.) Research Handbook on the Transformation of Higher Education. Cheltenham, Edward Elgar.

Coates, H. (2017). Productivity in Higher Education: Research insights for universities and governments in Asia. Tokyo: Asian Productivity Organisation.

Coates, H. (2020). Higher Education Design: Big deal partnerships, technologies and capabilities. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan.

Coates, H., Liu, L. Zhang, J., Jiang, F., Zhang, D. & Godinho, S. (2021). Next-generation assessment spurs smarter learning. Journal of Supranational Policies of Education, 13, 88-103.

Hazelkorn, E., Coates, H. & McCormick, A. (2018). Research Handbook on Quality, Performance and Accountability in Higher Education. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Hong, X., Liu, L. & Coates, H. (2021). Evaluating university social contribution: Insights and concepts from Chinese higher education. In: Managing Social Responsibility in Universities: Organisational responses to sustainability. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Skillsfuture (2025). About Skillsfuture. https://www.skillsfuture.gov.sg/aboutskillsfuture

Sung, J., Sheng, Y.Z., Liau, A.K., Xinhui, A.C., Liu, L. & Coates, H. (2021). Augmenting the role of higher education institutions in lifelong learning: Designing an indicator framework for global policy application. International Journal of Chinese Education.

Zhong, Z., Coates, H. & Shi, J. (Eds.) (2020). Innovations in Asian Higher Education. London: Routledge.

© HEFL 2025