Improving the governance of authentic thinking

Executive brief

- Universities’ leadership of academic integrity must be strengthened to embrace opportunities posed by contemporary artificial intelligence.

- Management information should be harnessed to help leaders promote integrity and step ahead of bad apples.

- Regulatory and governance reform is needed to bolster the assurance of learning, and confidence in university education and qualifications.

Fundamentally, higher education is about state-backed institutions warranting quality student learning. But this learning quality, and the value of university certifications, is under major threat.

University education rests on academic integrity, which in turn hinges on assurance of learning, and hence valid assessment. Contemporary artificial intelligence challenges much prevailing assessment. To underpin the value of university education, universities must strengthen assessment and assurance of learning.

To move forward, it is time to ignite an ‘integrity economy.’ Imagine if universities started each day ready to compete in an integrity economy, rather than one sculpted by faux research vanity. Bibliometrics made markets during the ‘world class university era,’ which is already fading news. Assuring authenticity of thinking is the sector’s future currency.

This briefing details immediate options for management and governance reform. It outlines new management information, and changes to governance architectures and regulation, that will safeguard sector integrity.

Hamish Coates and colleagues

The digital discombobulation of academic integrity

Wouldn’t it be wonderful if universities started each day ready to compete in an integrity economy, rather than one sculptured by faux research vanity? Bibliometrics made markets during the fading ‘world class university era.’ Assuring academic integrity is the sector’s future currency.

Fundamentally, higher education is about state-backed institutions warranting quality student learning. To step and stay ahead, universities must quickly define academic integrity in ways that can be measured, monitored, and improved.

This briefing articulates research conducted across several countries and years on leadership of assessment and integrity in the context of contemporary digitalization. It unpacks what generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) means for how academic leaders must ensure the integrity of qualifications. Academic governance is a remarkably resilient venture. It is both robust and flexible in adapting to new complexities. Yet this briefing shows contemporary academic governance is not well positioned or poised to handle integrity threats arising from GenAI, in particular threats related to authenticating student learning and qualifications. This briefing advances options for reform.

Now to strengthen education integrity

Effective governance of university education hinges on assurance of academic integrity. A synthesis of policies on university websites spanning several countries conveys that academic integrity generally encompasses ideas like honesty, fairness, responsibility, trust, and respect. Academic integrity is nuanced and varies over time and place. Yet many of its core ideas are global in nature, and inherent in the roles of scholarly communities. Academic misconduct is a contravention of academic integrity policies, regulations, and even laws. Universities govern academic integrity via policies and procedures that manage and penalize misconduct. Managing academic misconduct is essential to ensuring academic integrity, and to assuring integrity of any higher education experiences and qualifications.

Valid student assessment underpins academic integrity. Universities use assessment to identify, admit, manage, and progress students. Assessment is invariably the major touchpoint between students and their institutions. It lies at the heart, and certainly the endpoint, of any higher education qualification, yielding information which is aggregated to bestow credentials. Students and whole families live their lives around education assessment and its outcomes. Employers use assessment outcomes to select workers. Governments rely on assessment to develop professions and populations.

Yet the validity of much assessment is under massive strain. Social spacing arrangements implemented during the pandemic increased both physical and education distance between teachers and learners. Emergency online learning spurred higher rates of academic misconduct and academic shortcutting. Student approaches to study appear to have become more instrumental. These orientations are fueled by pressures baked into mass-participation systems, delicate labor markets and national economies, alongside more volatile migration and geopolitical settings. Amid all this change, around the world assessment reform has become vexed, lethargic, and devolved. This lackluster reality typically, and often for understandable expertise-based reasons, persists with little input from institution-level leaders. Indeed, leaders in hundreds of universities are often transfixed and distracted by research-weighted reputation rankings, and KPIs that require them to claw up reputational ladders. Limited attention to assessment validity results.

Contemporary digital developments have accelerated problems with assurance of student learning. Higher education makes, and changes, much that shapes the world, yet is itself often shaken by forces beyond its control. GenAI, like cheap travel and internet, is a case in point. AI has been around for decades, yet GenAI has proved quickly and widely disruptive. Around the world, governments, major organizations, and universities have scrambled to understand and control it. When used in smart ways by smart people, GenAI offers education all kinds of technological augmentation. Clearly, learning about and using such technology is itself relevant to much academic and professional work. Yet GenAI is hardly beneficial when used in academically unspecified or inappropriate ways. It is entirely feasible for students to use as yet unregulated GenAI to complete many common forms of assessment, without much individual cognitive involvement. Replacing thinking in this way alienates students from academic work and circumvents learning. There is a pressing need to strengthen academic governance of student assessment integrity in the GenAI era. This briefing charts two ways for doing this. First, it articulates new information to help university governors strengthen their work. Second, it outlines reforms that ensure effective uptake and use of this information.

Creating integrity information

Though governing minds are free to roam, academic leaders ultimately must rest their work on matters codified in artefacts such as agendas, papers, and reports. Challenges to education integrity outlined above make it essential to analyze and act on available information about academic integrity and related forms of misconduct. What new management information would help academic leaders improve their work, and hence the integrity of academic practice?

Since 2021, research has progressed to develop management information on the integrity of student assessment. This work evolved from a larger suite of work on assessment reform and innovation. It predated the wide scale, late-2022 public release of GenAI. In terms of method, the design involved multiyear analysis of research on academic integrity and misconduct, multi-institutional case study analysis, framework and data prototyping, qualitative validation with experts, and quantitative analysis of a broad sample of universities across world regions.

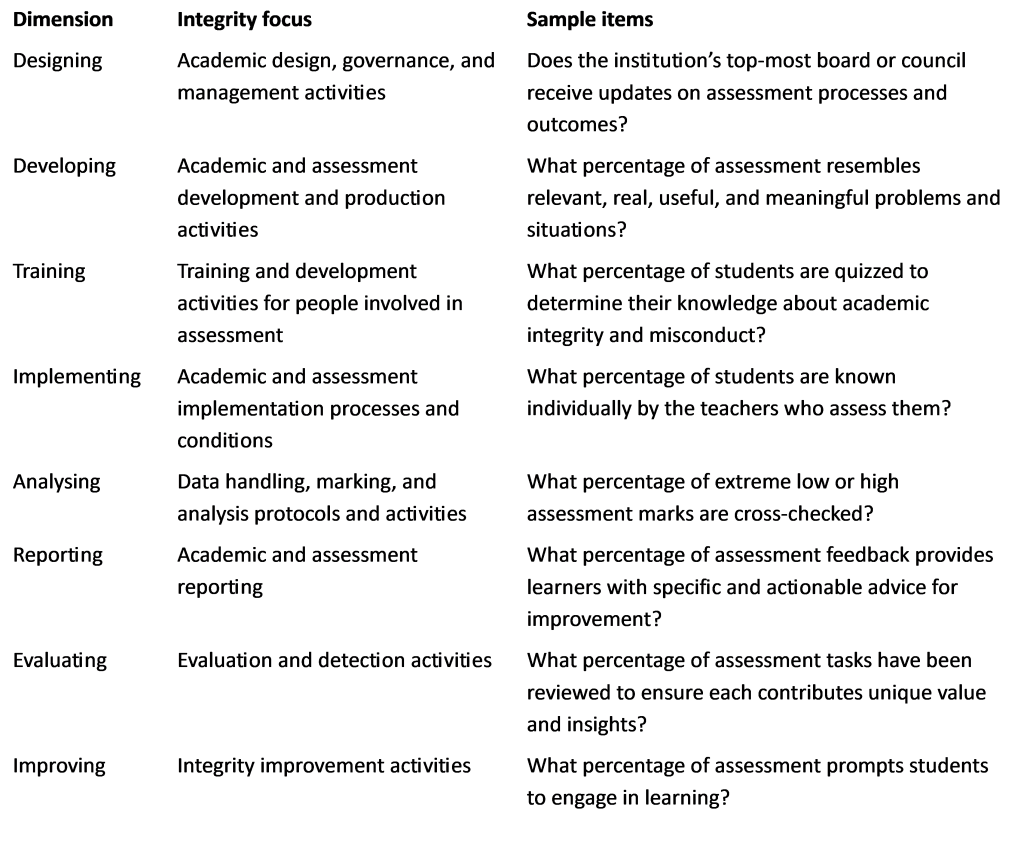

Overall, 130 survey questions were detailed and organized under eight dimensions of academic integrity. The dimensions were derived from a parameterization of higher education student assessment. The table shows that these dimensions include considerations pertaining to designing assessment, developing assessment resources, training and innovation, assessment implementation, analysis and reporting of assessment data, and evaluation and improvement. This parameterization is deliberately general so that it produces insights which synthesize educational, institutional, technical, and practical considerations across academic disciplines and levels. The table shows the summary focus of each dimension, the item pool size from which a subset is sampled, and sample items. A sample assessment is available at www.smarterlearning.global.

Table: Academic integrity indicator framework

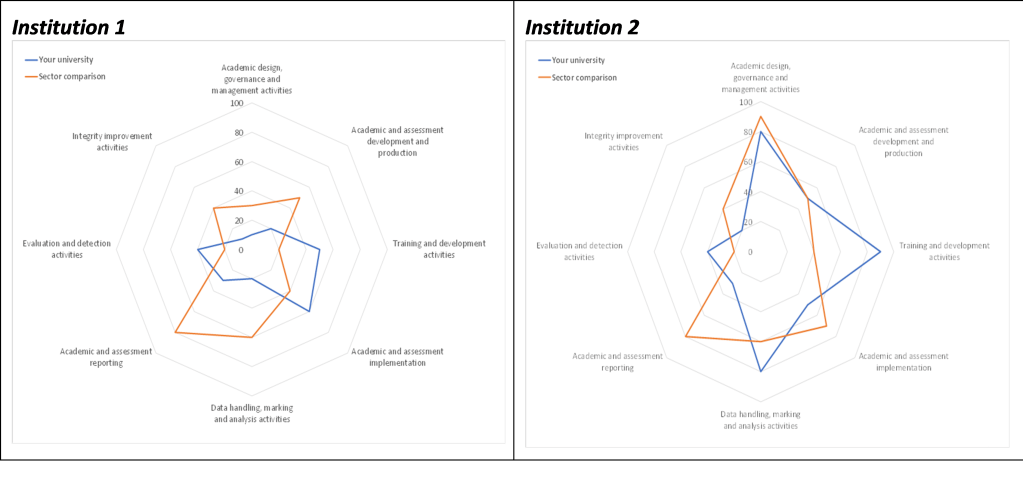

Management information was collected during international expert consultation, and from a subsequent pilot application by Australian institutions. The sample results shown in the figure depict different strategic settings for two institutions and sector benchmarks.

This validated management information provides academic leaders with oversight of areas where they and the institution are well prepared to manage opportunities and threats arising from contemporary forms of academic misconduct. Having data collected across an institution, preferably at department, discipline, or even course level, furnishes insight both at institution level and for important groups.

Figure: Sample academic integrity reports

Collecting such data is easy, subject to inertia and obstacles frequently associated with higher education reform. The solution lies in creating leadership appetite for such intelligence. Notwithstanding the intrinsic interests of leaders, pressures arising from contemporary ethical and integrity threats have, as earlier noted, created a tipping point which may well trigger that appetite. Right now, universities have an opportunity to act proactively, when the damage can be readily remedied.

Reinforcing leadership of integrity to outpace bad apples

Academic integrity information provides essential insight into assessment design and practice. But information is never by itself sufficient to substantiate a position or precipitate change. Broader reform is needed given the war universities are waging with a large and liberal pack of bad-apples – organized cheating companies, cybercriminals, and outsourcing firms. What is needed is a means of putting higher education institutions ahead of the bad apples peddling illegal and unethical services. Broader internal and external improvement is required to spur the proposed ‘integrity economy.’

Clearly, governance infrastructure needs updating. The cross-cutting nature of academic integrity and misconduct means a holistic institutional vision or position is required to make clear the philosophical position. Existing committee structures may be sufficient, or in the era of GenAI may need augmentation by standing or working groups with specific expertise in, and oversight of, academic integrity. Expertise on integrity and technology (in particular, cybersecurity) is essential and a new fixture in any governance capability matrix. Policies need to updating, as do underpinning procedures and guidance notes most institutions use to bring policy into practice. There is an obvious need to update platforms, resources, and institutional policies. Far from being a mere ‘vertical’ or ‘enabler,’ effective governance of digital technology is now intrinsic to higher education.

Governance architecture changes are merely performative unless an investment is made to train and educate people. To make this feasible requires a combination of internal stakeholders and those with requisite expertise. This may require dedicated training and resources for all members engaged in governance roles to ensure they understand their responsibilities, their remit, and the processes involved. Formal courses on AI governance have started to emerge. It is essential to work with professional and industry associations to ensure people graduate with needed technological and professional skills.

Change to governance operations is required. Assessment reform is imperative, and ongoing. Evaluating overarching course and delivery risk is essential. This would be aided by information from academic integrity indicators. Multifaceted approaches to cultivating integrity and technology literacy education are a priority. Fittingly, given the nature of the risk, translating methods from cybersecurity can help. ‘Red teaming,’ ‘ethical hacking,’ and ‘penetration testing’ all expose vulnerabilities and reveal areas that need development. These activities can close gaps between prevailing practice and policy, and emerging or frontier threats and opportunities.

Despite good intentions, internal change often requires external affordance. Universities are full of experts, yet challenges posed by unethical and illegal academic practices, and by GenAI, are global. These challenges seemingly overwhelm even the world’s best resourced organizations and governments. Higher education is invariably difficult to reform, not least due to the resilient nature of academic governance. Limited transparency of academic misconduct makes change fraught. Benchmarking and collaboration play essential roles. This places additional pressure on quality and regulatory agencies to spur changes in practice. Ultimately, generating a reputational economy based on academic ethics, rather than research-oriented reputation, paves a useful path forward. Nascent and formative progress is being made to stimulate and guide regulatory reform. Transparency is an important change-driver. Concerningly, the world lacks a recognized forum for discussing this topic. There are meetings about universities, about governance and about GenAI, but there is no sustained and inclusive forum for sharing and advancing analysis of important intersections of these topics. This is troubling given the international nature of the phenomena in play. Usefully, given this void, a series of regulatory agencies have cooperated to form the Global Academic Integrity Network (GAIN). In Australia, the higher education regulator has asked institutions to report what they are doing to tackle GenAI’s implications for academic and qualification integrity. The best intentions and concerted efforts of higher education accountability agencies are likely to have muted impact, however, given the lagging nature of reform, distance from academic practice, and the situation’s truly global nature. Nonetheless, creating dialogue and sharing practice is a necessary step in system reform and eventual practice reform.

Edging leaders back in front

In the face of major threats to academic quality and integrity, this briefing has articulated research conducted to present the need for new academic integrity information and approaches to academic governance. The higher education sector has embraced and institutionalized digitalization; perhaps as much as, if not more than, any industry sector. So far, universities have seen off catastrophic or existential disruption. Such history portends that GenAI will follow the same path, though as an ‘apex technology’ it is surely a non-ignorable force for change.

Leadership of academic quality lies at the heart of higher education. That leadership needs to grow to reinforce integrity of assessment of student learning which lies at the heart of ensuring authenticity of higher education qualifications. The pandemic socially spaced learners and teachers. GenAI has facilitated forms of intellectual alienation which have seeded further transactional distance between how learners think and their education. This spurs an urgent need for governance reform that safeguards against risk, and plans for future education transformations.

Working on academic misconduct is important but difficult. Handling often murky ethical and legal matters can be tricky, even for experienced academics and managers, and especially when issues are dispersed throughout large and complex institutions. Such work is particularly fraught given the reputational economy in which universities compete. Indeed, widespread entrenched fixation on research performance and rankings, especially when these matters serve as presumed proxies for education quality, can mislead, distract, disorient, or stifle investment in academic integrity. Education excellence and qualification integrity depend on robust, efficient, and relevant assessment. It is now time to ignite a flourishing ‘integrity economy’ in higher education.

Further reading for inquiring minds

This briefing was written by Hamish Coates, with input from Angel Calderon, Gwilym Croucher, Steve Godinho, Fangzhou Jiang, Liu Liu, Dan Zhang, Juan Zhang, and others.

AdvanceHE (2024). Starting the conversation about AI and governance. Accessed from: https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/news-and-views/starting-conversation-about-ai-and-governance

Australian Institute of Company Directors (AICD). (2024). A Director’s Guide to AI Governance. Accessed from: www.aicd.com.au

Beaton, J., Xi, G. & Coates, H. (2022). The digitalisation of higher education: The transformative role of EdTech. In: Dee, J.R. & Leisyte, L. (Eds.) Research Handbook on the Transformation of Higher Education. Cheltenham, Edward Elgar.

Center for University Governance and Reputation (CUGR). (2024). Artificial Intelligence and University Governance. Accessed from: https://en.unav.edu/web/direccion-estrategica-de-universidades/inicio

Coates, H., Liu, L. Zhang, J., Jiang, F., Zhang, D. & Godinho, S. (2021). Next-generation assessment spurs smarter learning. Journal of Supranational Policies of Education, 13, 88-103.

Coates, H., Croucher, G. & Calderon, A. (2025). Governing Academic Integrity: Ensuring the authenticity of higher thinking in the era of generative artificial intelligence. Journal of Academic Ethics.

Global Academic Integrity Network (GAIN). (2024). Global Academic Integrity Network. Access from: https://www.globalacademicintegrity.network

Heyneman, S.P. (2019). The Ethical Underpinnings of World Class Universities. International Journal of Educational Development, 23(5), 6-11.

Institute of Education (IOE). (2024). Beyond the Horizon: The Global Development of AI-Empowered Higher Education. Beijing: Tsinghua Institute of Education.

Maassen, P. (2017). The university’s governance paradox. Higher Education Quarterly. 71, 290–298.

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). (2023). Generative AI. Accessed from: https://oecd.ai/en/genai

White, J.D. (2023). Academic integrity in the age of AI. Educause Review.

World Bank (WB) (2023). Generative Artificial Intelligence (English). Accessed from: https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/099526207072313067/idu05c8fad510efb8045750ad2b0120b3b2ff8a2

© HEFL 2025