Regulatory reform for university success

Executive brief

- It is time to crank regulatory policy to give Australian higher education a vision and swagger focused on success.

- Prevailing regulatory arrangements only go halfway to those which were always intended, are no longer fit for purpose, and have normalised perversity.

- Lighter and more effective regulation would flow from fresh dialogue, participants, and evidence.

What is regulated matters because it is allowed to play. At the dawn of the millennium Australia took giant steps in establishing a university quality agency, followed by a more powerful standards regulator in 2011.

It is time for further policy innovation, as is rendered obvious by the torrent of discourse about higher education relevance and value. Current regulatory arrangements have wandered far from education foundations, risk distorting integrity and growth, and are yielding diminishing sectoral and community returns.

Though familiar acronyms can seem cozy, current arrangements are transitory, even peculiar and precarious. Value can be unlocked by completing the trajectory designed two decades ago. New information will inspire new dialogues among broader contributors. Australia should mature its regulatory approach to focus more on teachers, students, learning, outcomes, success and contributions. Attention can then be sharpened to ensure that students get the education they need to succeed.

Hamish Coates

Proving education real for students and the world

Regulation of higher education stirs butterflies in the tummy for only a very select few. Even most people who are aware of it tend to shelve it below shivering at an isolated bus stop on a dank and gusty night. Yet its consequences are enormous. What is regulated matters because it is allowed to play. The regulatory toolkit mandates guardrails by which universities, academics, students, and ultimately professionals must play.

Along with pioneering Tall Poppy Syndrome, since the 1980s Australia has, paradoxically, served somewhat as a global petri dish for spawning novel forms of higher education regulation. Aussies like to give things a whirl, reckon she’ll be right, and thirty years ago needed to firm a solid and quick means for assuring the vibrancy of an internationally exposed system. At the dawn of the millennium Australia took giant steps in establishing a university quality agency, followed by a more powerful standards regulator in 2011. The world looked, inquired, poked, and emulated. Regulators regulated, and tinkered to adapt, accommodate, and fine-tune.

It is time for further policy innovation, as is rendered obvious by the torrent of global discourse about higher education relevance and value. Current regulatory arrangements have wandered far from education foundations, risk distorting integrity and growth, and are yielding diminishing sectoral and community returns. After 15 years of consolidation, regulatory policy should take further giant steps that advance more productive futures for universities, and for the communities they serve.

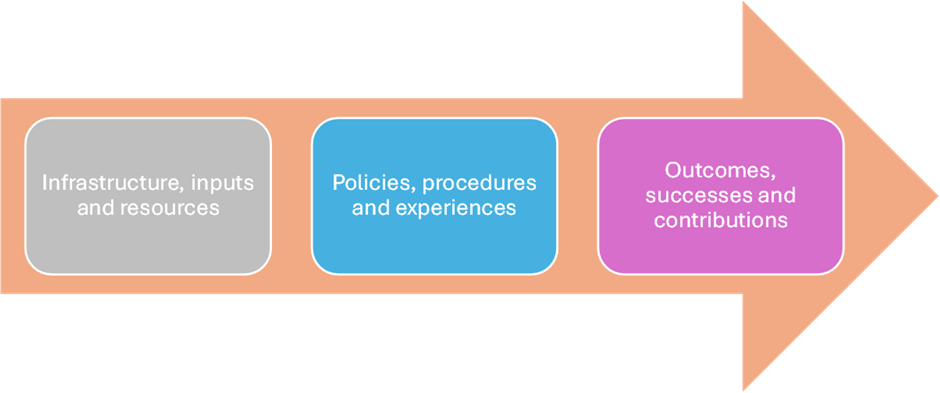

Value can be unlocked by completing the trajectory designed two decades ago and moving to an approach focused much more on teachers, students and learning. Attention can be realigned to ensure students get the education they need to succeed. This means shifting focus from campus resources and administrative procedures, which are helpful but rarely necessary or sufficient for excellent education.

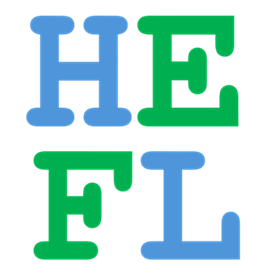

Figure 1: Advancing regulatory maturity

There are obviously different ways to design and activate this agenda. Among the options one seems clearly first-rate compared with others. This better option resonates with the academic core, is parsimonious, and will do much to build confidence and value in the sector. It involves making higher education for students. This briefing clarifies options and charts a way forward. Australia remains a useful case for dipping toes into novel regulatory ponds as it has a system which is international, mature, entrepreneurial and forward looking.

The clutches firm then tighten

Higher education regulation can feel like it echoes across the ages, but it has evolved significantly in recent decades, along with changes to external and internal practices. Regulation has wandered far from its academic origins into diversions that were not necessarily planned or intended.

For many decades, higher education in rich countries relied on what is widely and colloquially called the ‘sniff test.’ This universally uncodified assessment invariably involved a prestigious academic providing judgement on whether a university passed muster.

From the 1990s many countries developed internationally recognized domestic quality arrangements. For the most part, these were built from the idea that quality could be viewed through the lens of ‘fitness for purpose,’ with academic experts evaluating purpose and fitness.

As tertiary education sectors around the world expanded, templates emerged to frame these academic experiences. The templates were then regularized, routinised, and gamed. At the outset, this really was about ‘quality’ rather than ‘regulation’ as there were typically only government institutions, and most had distinct places in stratified systems.

Eventually, as ‘systems’ grew into ‘quasi-markets’ and institutions proliferated, governments lost confidence in the academic nature of the exercise. Governments turned the work over to university administrators and civil servants.

Australia zoomed ahead of the global pack when it established a standards- and risk-based approach to regulating higher education. Rather than defer to expert judgement about academic practice, institutions and courses are appraised against uniform standards. Academics may be marshalled to proffer opinion, but the discourse style invariably favors consultants and lawyers.

Turning the returns

There are dangers for all in having quality wandering in a corporate exoskeleton which hovers around the teachers and students who make it real. No doubt, universities like any institution need ongoing rectification. But risk grows to long-term flourishing when regulation itself narrows the strategic gaze.

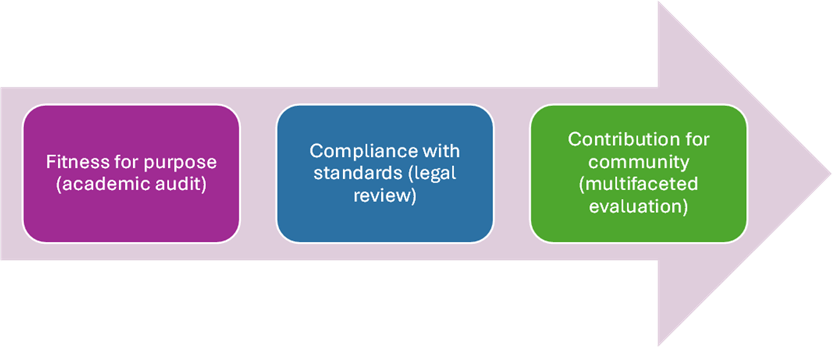

Regression to minimum standard is normalized. Invariably, as argued during the design of Australia’s regulatory reform, without clear incentives around escalating standards, compliance sinks to threshold levels. A skerrick above bare minimum is sufficient and the only administratively rational position.

Education is commoditized not created. Education experiences and resources are standardized to avoid risks associated with contextuality and intellectual experimentation. Education resources and experiences are coded into uniform digital resources on digital platforms. This is weird, for playing with complex ideas is exactly what university is about.

Teachers and learners are alienated. Accrediting education without students and teachers estranges those who are core to its production. This is a problem, because education with only minimal or performative teaching and learning is not really education at all. Given the sophistication of contemporary information technologies, it may well flip to an interface among student/university/faculty machines.

Sluggish improvement abounds. Without timely real-world insight into quality, education gets pretty hard to improve. Administrative documentation can only ever yield a partial, often highly curated, picture. That may be fine when a small club of universities effectively self-regulate, but is far too thin in an internationally open market. Poor and even bad practice proliferates.

One clear danger flowing from an overly administrative approach to higher education quality assurance is that those who should be watching – leaders, regulators, policymakers – take their eyes off important balls. Corporate machines and managers control the risk, albeit by subverting the essence of education itself.

Figure 2: Regulation narrows strategic gaze

Rolling pointy dice

Regulation of higher education is a young and creative field, nowhere near as entrenched as control of liquor, automobiles, weapons, or schools. Diverse regulatory models are distributed around the world, varying by country, profession, culture, and even institution. It is always easy to find comfort in familiar acronyms, yet it is reasonable to assume regulation will continue to evolve and may look very different in just a few years. Opportunity abounds in small and big systems alike.

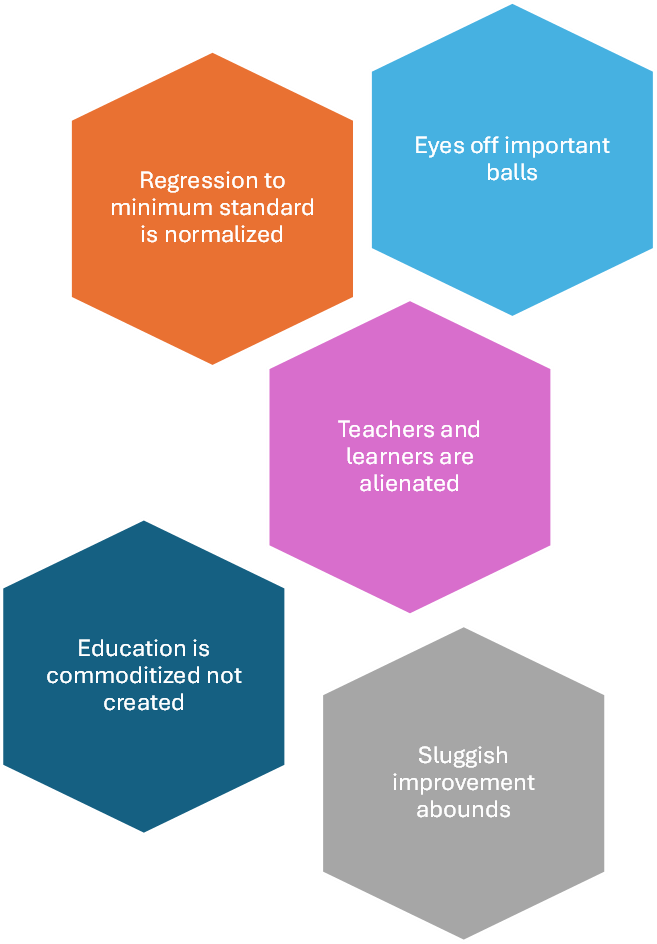

One option is that regulation shrinks, fades, or evaporates altogether. This may be appealing to privateers and landed universities alike, yet life gets tougher when anarchy prevails. Without protection, even powerhouse universities in prosperous countries can be swamped in open global waters. Variations in substance and performance can be enormous, as is obvious to anyone who touches transnational online education. Even international free trade zones have built regulatory along with campus architectures.

Another option is that regulation lopes along more or less as is, perhaps with convergent administrative advance. Rules can be clarified to boost administrative efficiency. Policies and procedures can be consolidated, as can hiring, platforms and resources. One big institution could underpin a number of clones. Tougher powers can be granted to scorch squabbling. Beyond those who have lavishly exploited such arrangements, this would seem to hinder the sector and yield diminishing future returns.

Reverting to the global regulatory norm is an easy option. By this logic, institutions would write their stories, eminent reviewers would critique, then regulatory would pronounce. Most countries still regulate universities in this way. While defendable, this approach is hardly the most appealing given sectoral advances, changes in operating platforms, and how the world keeps changing. The trust which oiled such processing in earlier days proved hard to scale.

Of course, higher education could further align its regulatory methodology with other sectors. Movement in this direction has been made over the last decade in Australia, not least to enable a broad array of non-specialists professionals to participate in the process. But higher education is itself sui generis. There are limits to how much academic essential oil can be maintained if its regulation is spread among more universal approaches.

Looping back to build and prove the value of the core would seem a smart way forward. Build on current rudiments and tweak the toolkit. It seems obvious to suggest education regulation should reference data on teaching and learning, and the value of education in the community. As noted above, this was always the plan, but the regulatory reform was never finished. It is time to move, to keep universities growing.

Figure 3: Regulatory reform options

Sprucing the core

It is feasible, and many would argue urgent, to regulate universities for education and communities. This was always the intent until Australia’s national imagination became mired in convergent litigation. Moving regulatory policy in this direction means leaping beyond infrastructure and procedure to instead focus on outcomes, success and contributions. It doesn’t mean meddling in academic life and affairs, rather consideration that such things matter.

Figure 4: Sprucing the regulatory agenda

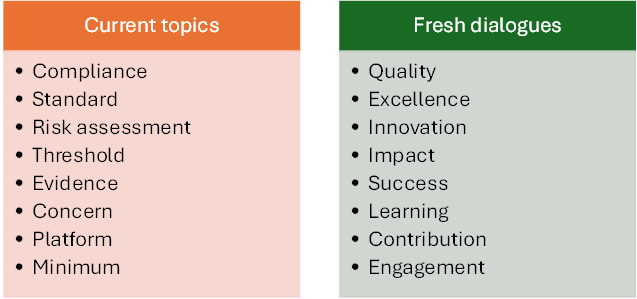

Changing the language is always the first step. That step includes building a raft of standards which concentrate the mind on operations and resources. Such standards can funnel energy more dynamically. They constitute an investment in making universities zoom.

After two or three regulatory cycles for incumbent institutions, tilling the same linguistic and epistemological soil yields diminishing returns. That is so even if regulatory cycles claim to proportionately apply risk-based logic and evidence. More venturesome, impactful public dialogue would be helpful. That’s how to breathe fresh life into the directions which higher education needs to travel.

Figure 5: Freshening the dialogue

Changing conversations helps people swill around, which is what gives education life. Venturing ideas and institutions and sectors into the future means imagination, trust and confidence. This is the work of entrepreneurs and educators, of researchers and learners. It follows that academics, students and communities must be brought in from the cold. Critical academics are inherently the basis of education quality, troublesome as they may be to ‘massive higher credentialling machines’ which large universities have grown to resemble. As a matter of principle, learners who have skin in the game should help co-produce how learning is designed, taught and assessed. It is impossible to outsource ‘quality matters’ to silicone chips, to consultants, to lawyers, to general managers, to governments. That would be ‘pseudo-quality,’ or perhaps ‘performative quality.’ Quality is the domain of students, teachers, and professions, even (and especially) in the world’s largest and perhaps most reputable higher education systems.

A risk-directed approach to regulation hinges on the topic and interlocutors, and ultimately the information available. Making, then using, novel information about education will play a huge part in advancing the sector’s contributions. Universities are swarmed by data, yet lack of creative attention to information repositories means they have, like custard, grown lumpy in parts and watery in others. No amount of actuarial bibliometric bragging can make up for the dearth of data on education capabilities, partnerships, integrity, impact and value. Twenty years ago it was asserted that education information was too hard to produce. This claim is no longer sound.

These policy advances will lighten and improve the impact of higher education regulation in Australia. In doing so Australia will chart futures which, as in earlier iterations of regulation, the rest of the world can channel. After all, what matters is that universities help students succeed in demonstrably excellent ways, and that universities change the world. Regulation becomes zombie-like if it fails to resonate with the sector and chart prosperous directions.

Schmoozing ahead

Governments spanning the world’s advanced economies have broadcast the need for universities to embrace more learners than ever before, to provide education experiences which help students succeed, and to keep people progressing in ways that propel thriving careers. Three decades of globalization and digitalization have wrought head-spinning changes to higher education, but not yet the reform that ensures students and communities fully realize the experiences and benefits universities have to offer.

Now is the time to trigger this reform and shape higher education around the needs of education and communities. Making higher education for students has an important role to play. There is much to be done to get moving. This goes well beyond brilliant ideas from technologists, beyond branding and marketing departments, and even beyond the reach of regulators. Striding in this direction will take a lot more than cutting operational complexity, tapping revenues, and shaving costs. New vision, dialogue, and data are needed. Real change will flow from reforming regulation to ensure universities more fully service the needs of students and their communities.

Further reading for inquiring minds

Coates, H. & Matthews, K. (Eds.) (2018). Frontier perspectives and insights into higher education student success. Special Issue of Higher Education Research and Development, 37(5), 903-1094.

Coates, H. (2010). Defining and monitoring academic standards in Australian higher education. Higher Education Management and Policy, 22(1), 1-17.

Coates, H. (2018). Postsecondary Punters: Creating new platforms for higher education success. In: Weingarten, H., Hicks, M. & Kaufman, A. (Ed.) Beyond Enrolment: Measuring Academic Quality. Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Coates, H. (Ed.) (2018). Navigating higher education to enhance student success. Special Issue of International Journal of Chinese Education, 7(1), 1-173.

Coates, H. Woodhouse, D. James, R. & Sadler, R. (2009). Setting and Monitoring Academic Standards for Australian Higher Education: A discussion paper. Melbourne: AUQA.

Coates, H., Kelly, P. & Mahat, M. (2016). The regulation of standards in higher education. In: Meyer, L.H. (Ed.) Oxford Bibliographies in Education. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Coates, H., Kelly, P. & Naylor, R. (2017). Leading online education for student success. International Journal of Chinese Education, 6(1), 105-126.

Coates, H., Weerakkody, U., Jerez, E., Wells, M. & Popenici, S. (2018). Transparency is the lynchpin for higher education success. In: Cantwell, B. Coates, H. & King, R. (Eds.) Handbook on the Politics of Higher Education. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Kelly, P., Dollinger, M. & Coates, H. (2017). New directions for quality assurance: Transparent outcomes for industry collaboration, research training and student success. Higher Education Evaluation and Development, 10(1), 31-51.

Kelly, P., Dollinger, M. & Coates, H. (2017). New directions for quality assurance: Transparent outcomes for industry collaboration, research training and student success. Higher Education Evaluation and Development, 10(1), 31-51.

Naylor, R. Coates, H. & Kelly, P. (2016). From equity to excellence: Reforming Australia’s national framework to create new forms of success. In: Brett, M. Harvey, A. & Bernheim, C. (Eds.) Student Equity in Australian Higher Education: Twenty-five years of A Fair Chance for All. Dortrecht: Springer.

© HEFL 2025