Proving the success of higher education

Executive Brief

- Postsecondary punters are people who place bets on higher education.

- Reliable information is needed to clarify and prove the value of higher education, and to improve investments and outcomes.

- Improving how people invest is essential for students and graduates, and more broadly for industries, organizations, professions, and communities.

Higher education is a huge industry and finance firms around the world are active in many investment plays. Most postsecondary punting happens in humble family homes by people wagering higher education has a part to play in helping them or their loved ones succeed.

Improving such punting is essential for students and graduates, and more broadly to industries, organizations, professions, and communities these people will lead.

To propel growth, it is necessary and perhaps imperative to advance a progressive agenda for academic quality. Higher education must move beyond seeking asylum through coded opacity that fails to disclose the sector’s full brilliance and offer.

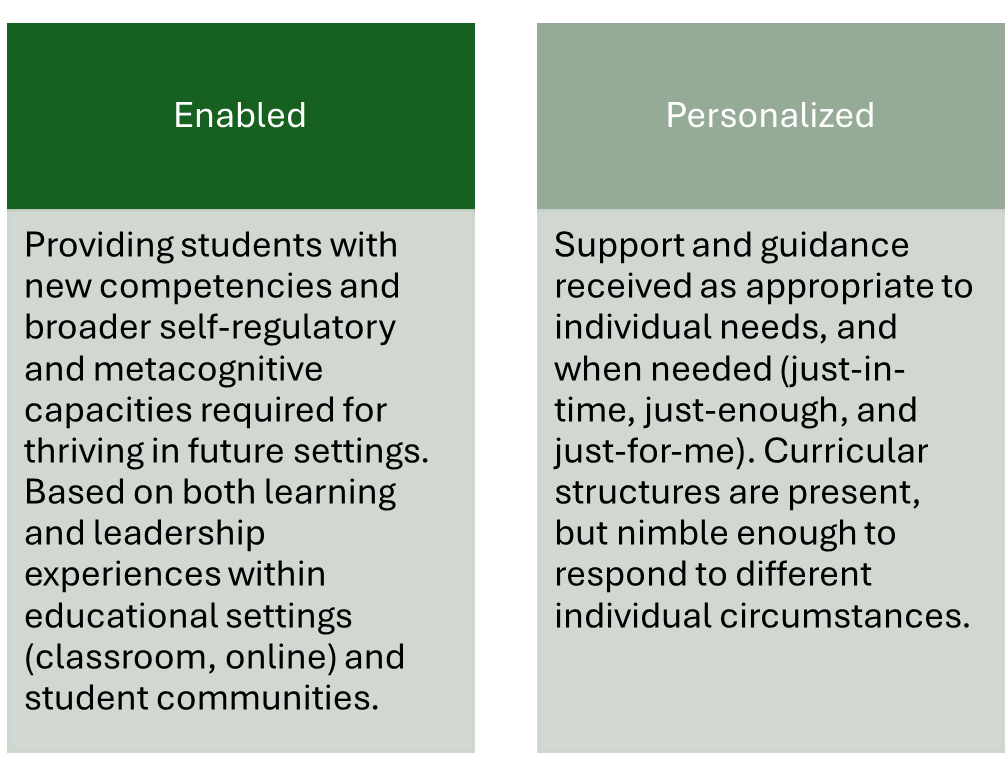

Research has defined Nine Student Success Qualities (9Q) which step beyond prevailing terms too mark out worthy agendas that helps students succeed:

| Discovery | Achievement | Connection |

| Opportunity | Value | Belonging |

| Identity | Enabled | Personalized |

New information and reporting platforms will clarify higher education and prove its value, and to improve punters’ investments and outcomes.

Hamish Coates with colleages

Better bets on tertiary futures

Postsecondary punters are people who place bets on higher education. Higher education is a huge industry and finance firms around the world are active in many investment plays. Most postsecondary punting happens in humble family homes by people wagering higher education has a part to play in helping them or their loved ones succeed. Improving this kind of punt is essential for students and graduates, and more broadly to industries, organizations, professions, and communities these people will lead.

At least once, people should ask what value higher education might add to their lives. People should consider how higher education could enlighten them, could make them a more capable professional, or a better citizen. In advanced societies it is expected that such questioning is almost ubiquitous, that most people should make such inquiry.

Unfortunately, it is also almost universally clear that hardly anyone has access to good quality information needed to buy higher education. It is unclear where helpful information can be easily sourced, who governs such advice, and how higher education institutions can use data to improve. The problem endures for those who engage in higher education as they bump through bureaucracies, sit lonely in crowded lectures, and seek personalized insight from teachers and institutions to help them succeed.

As higher education has expanded, so too have widespread calls for reliable information on its value. But there remain core facets of the academy about which little is known, and available information is often difficult even for specialists to interpret. Traditional

disclosure arrangements evolved for highly regulated and supply-driven forms of provision. Shifts to far larger and more competitive contexts require radically new disclosures. To guide and sustain future growth, more must be done to report and affirm the higher education sector’s value and contribution. It is important that people have access to insights which sustain confidence and support. This means moving beyond myths and rituals that may feel ingrained, yet fail to prove value. It means creating new data collections and reporting mechanisms, and sparking new cycles of contribution and improvement.

To propel growth, it is necessary and perhaps imperative to advance a progressive agenda for academic quality. Higher education must move beyond seeking asylum through coded opacity that fails to disclose the sector’s full brilliance and offer. How people talk, measure, and report on quality is outdated. Set-piece conversations do little to make an inquiring public, industry or government more informed, satisfied, or poised to succeed. Major new reporting platforms are required to clarify higher education and prove its value, and to improve punters’ investments and outcomes.

Buying higher education

Delving a little into ‘buying’ spurs simple yet always controversial innovation. Much has been invested in trying to understand and influence how people buy products and services. Buying is a complex endeavor, even for small purchases. It gets even more complex when higher education is the thing about to be consumed. But there are a few fundamental processes at play. Basically, buying steps through awareness, searching, deciding, and purchasing. This briefing delved into the first two steps.

Becoming aware of a need or want is an obvious initial step in buying. The formation of such awareness is complex. It may not be rational, obvious, or sequential. Research into higher education consumption suggests a range of cultural, familial, personal, and educational forces shape decision-making. But increasingly, any fine-grained deliberations appear swamped by much broader socioeconomic forces. Demand for higher education continues to grow. A bachelor’s and increasingly master’s degree is the passport to most forms of professional, or even much skilled, work. In fast-growing economies it is the ticket to the middle class. The value of such credentials is expanding as economies mature. The growing scale of higher education underlines the importance of getting ‘awareness formation’ right. This is true for all punters, and particularly pressing for people from countries or communities without traditional access to tertiary education opportunities.

Awareness of the need for a service like higher education launches a search process that identifies options, and for each option salient parameters and attributes. First, what options or various higher education services are on offer? Next, how should we evaluate these options, and what parameters are relevant to consider? Then, what information on each parameter is helpful for deciding? Expertly run procurements might unfold in such a sequence, but in practice for most people such searches are likely scatty, sub-rational and non-articulated. It is unfair to frame potential higher education consumers as experts. Most are first-time buyers. Given the demography of the world’s high-growth markets, most aspirant consumers have little personal or familial experience of the industry. And this is an area in which even industry experts can be flummoxed. It is sometimes asserted that education, like eating, is a credence good, underlining the need to carefully frame the information that plays into people’s deliberations about buying higher education.

These brief forays affirm the great significance of always seeking to do better in making people aware of higher education, and in improving information that can help people with buying. These are important matters for people and their communities. The price of failure is high. It is impossible to be too deterministic about education, where experience matters along with substance. But evidence shows people are better off if they have opportunities to participate in higher education. And surely economies benefit most when the most interested and able people are schooled into professions. The nature and disclosure of information about higher education matters a great deal.

Craving confidence

Over the last three decades, much has been done to help people buy higher education, and to afford confidence in the decisions they have made. Most countries have required greater financial disclosures, conducted innumerable policy reviews, spent billions on consultants, ramped-up media attention, encouraged more public-spirited academic reporting, created various advisory and information networks, and expanded personnel training. Yet to date, such efforts have proved inadequate. The ‘quality movement’ provides an interesting case study of the shortcomings of such attempts.

In advanced economies, the ‘quality period’ started in the 1990s as higher education expanded beyond elite preserves. Governments sought assurance that public funds were being administered to deliver education of sufficient quality for their growing populations. Quality is a pervasive and expansive idea. It touches every facet of university life in different and changing ways. The dominant focus during this period was mainly educational and administrative functions rather than research or broader engagement. The main approach might be characterized as ‘internal self-evaluation followed by external peer review,’ the latter facilitated by some form of quality agency. Governments set up these agencies and had reasonably close relationships with universities.

This quality agenda achieved much. For instance, it helped to build academic management systems within institutions, to create large volumes of ‘enhancement’ work, and to ensure institutions led academic matters in ways ‘fit for purpose.’ Quality-related work spurred system-wide and international alignments, and sector-specific infrastructure and discourse. The quality period helped professionalize and safeguard higher education.

In recent decades, this approach to quality has lost its dominant position, and increasingly much of its shine. Quality agencies in several countries, including the United Kingdom and Australia, have been replaced. Similar agencies in the United States seemed to be bursting at their existential seams. The focus on peer review led to variation in defining and applying standards, and overusing the words ‘appropriate’ and ‘concern’ to avoid terminal relativism. The focus on institution-level processes yielded diminishing returns and failed to account for outcomes that really matter. Production of (undoubtedly heavily redacted) industry-centric reports failed to yield information for postsecondary punters, particularly of the kind increasingly viewed as normal in broadband-enhanced societies. The ‘insider’ perspective evolved from collegial arrangements and stumbled seriously in more competitive and commercial settings, including with emerging for-profit and private forms of transnational provision. Further, quality agencies set up to run the processes typically had no or weak regulatory powers that could enforce any identified improvements. In general, the ‘quality period’ might be seen as setting the foundation for shepherding higher education institutions in advanced economies from elite to mass scale. More has been seen as required to guide progress in more universal, competitive and complex times.

Shortcomings in the higher education sector’s own quality agenda fueled anxieties, particularly among those outside ‘the university club’ where, arguably, it does still work. These anxieties spurred workarounds and new solutions. As dominant funders of higher education, governments clarified and strengthened their regulatory powers. Consumers sought information from new market-targeted reports on institution performance and, in particular, on research and reputational rankings. New market entrants, in particular for-profit private institutions, used commercial research to strengthen their market plays. Business and community stakeholders continued to flounder in exasperation at the accidental ways they remained forced to engage with universities. Of course, separate accreditation exists for professions, with its own complexities.

As even this summary conveys, bewildering information has proliferated about many facets of higher education. This unravelling has ignited confusion, not clarity. No solution thus far has yet addressed the aching need for effective, sophisticated, and comprehensive disclosures that help people make informed decisions about their initial and ongoing engagements with education.

Revealing success

Information on higher education abounds, of course, but is of varying quality and relevance. It can be difficult for even experts to decode, let alone exploit to articulate a transformative higher education experience. Typically, data has a ‘supplier-centric’ tinge to it, providing results from a distinct data collection on an entire institution’s past, rather than advice as to how different parts of that institution might help an individual’s future. What is needed is to convey to each person what a successful higher education experience looks like.

This state of play creates several problems. Most particularly, individuals cannot inform, let alone optimize, how they might invest in higher education. As well, people and institutions providing higher education cannot communicate the value of what they do. Society overall can fail to recognize the value of the higher education system, with consequences for constrained government funding, reduced community perceptions of value, and attenuated engagement with other industries and businesses. Lack of good information can induce failure. The situation gets more serious when considering transformations shaping so many facets of higher education, like regulation, markets, staffing, students, institutions, and governments.

Next-generation information is needed to help people engage successfully with higher education. A first key step in this quest to provide better information is to identify what should be reported. A suite of ‘success indicators’ would yield powerful information on how higher education can help people and communities succeed. Research has shed light on the nature of success in higher education, and how it can be measured.

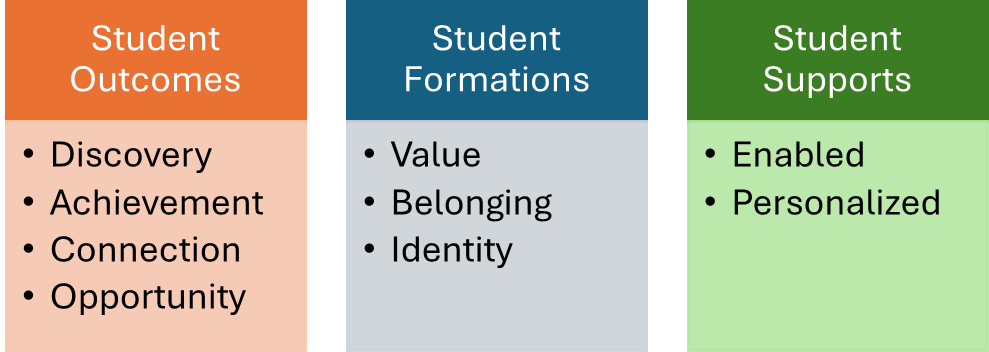

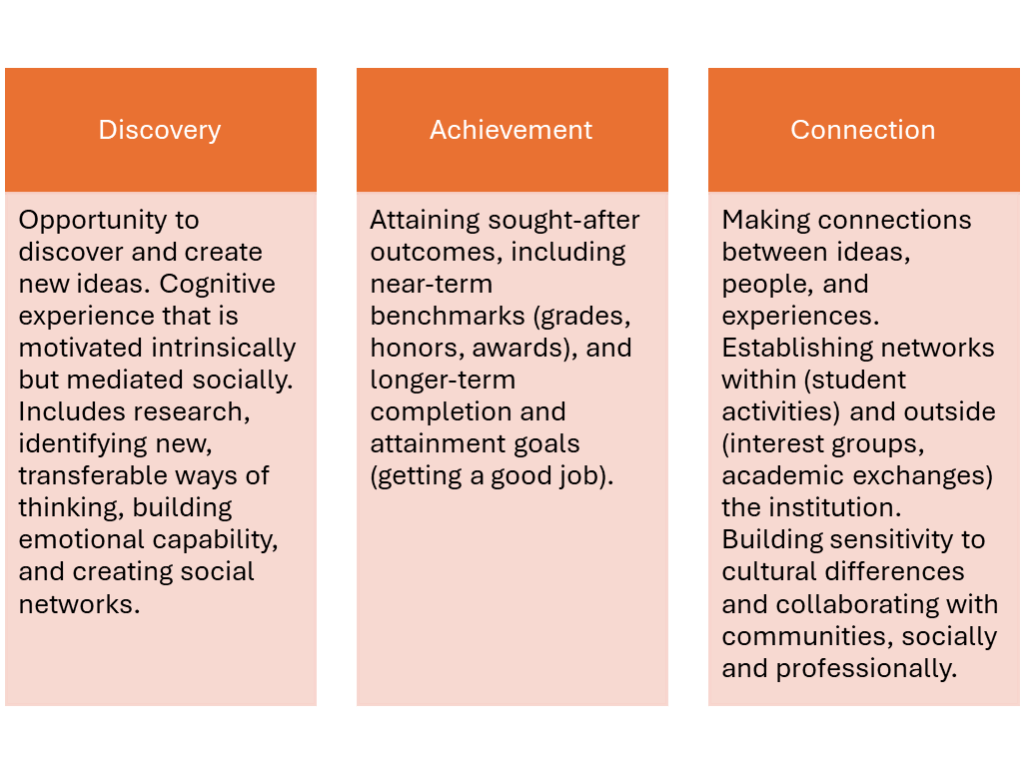

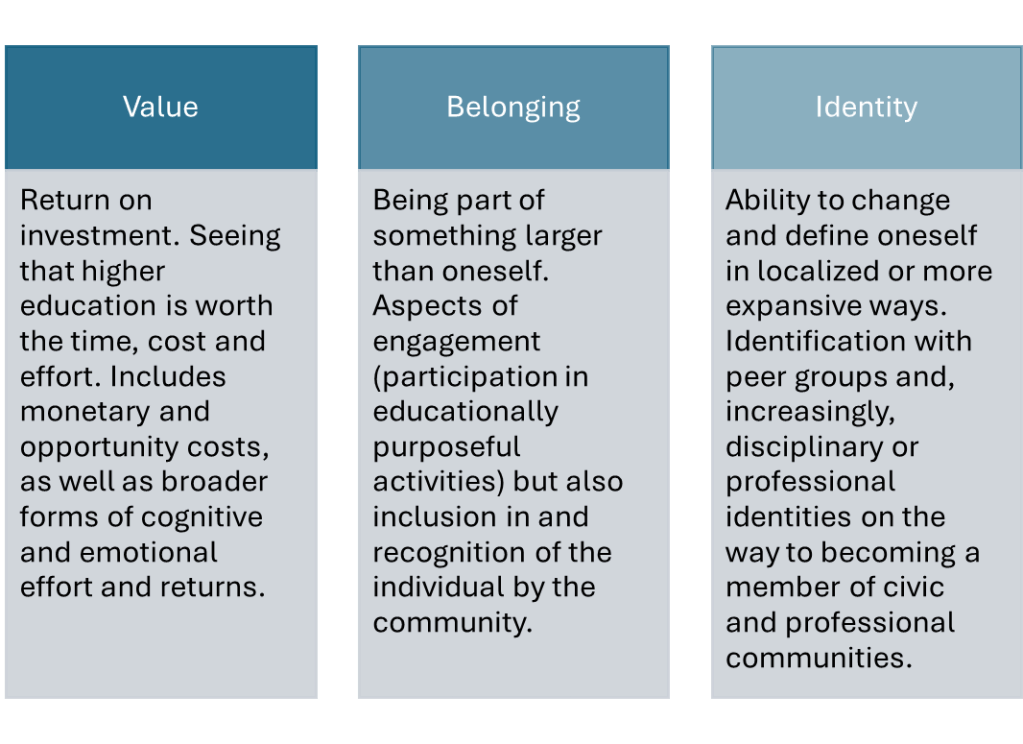

This research deconstructed student success into nine qualities. Tables 1 to 4 present the nine qualities. The qualities mark out a suite of worthy agendas, and carry potential to create discourse that helps students and their institutions succeed.

Table 1: Nine Student Success Qualities (9Q)

Table 2: Nine Student Success Qualities – Outcomes

Table 3: Nine qualities of a successful student experience – Formations

Table 4: Nine qualities of a successful student experience – Supports

Importantly, these qualities step beyond prevailing terms used to define and operationalize student experience and related constructs. For instance, while ‘student satisfaction’ has become somewhat entrenched, there is ample evidence that besides stamping out woeful practice it offers substantially diminishing returns to improving higher education. Worse, it sucks energy and attention away from things that really count. Even ingrained phrases such as ‘teaching quality’ and ‘student support’ and ‘student services’ are becoming less relevant as team-based computer-mediated teaching and facilitation becomes more widespread, as evidenced by near-universal adoption of learning management and other enterprise-learning systems. The Nine Student Success Qualities are broader than frequently espoused, though rarely measured, ‘graduate attributes.’ They instead project qualities that signal new, co-created conceptualizations of higher education.

Next-generation reports

New platforms are required to report information in ways that help people succeed. Having the right information is necessary, but not sufficient, for improving how people buy higher education. Information already abounds in higher education, though as identified above, there is substantial scope for repackaging it. Better reporting is also required.

What are the problems with current platforms? There are many. It is common for reports to present highly diffuse information on a narrow range of institutional (mostly research) functions. Information is often lagged, sourced from third parties, often annual, unverified or of unknown validity and reliability. Such information is often presented online in static ordinal lists without regard to interpretation or consequence. Reports may be provided without full disclosure of political or commercial interests or intentions. The current reporting landscape is just too confusing, even for experts, and especially for postsecondary punters.

There is a need for ‘next-generation’ reports, delivering information that is more dynamic, and hopefully more robust. Reports should unfold at two parallel levels. The first is institution- or program-level benchmarking tools for industry insiders like ministries and institutions. Second, there is a need for nuanced platforms particularized to the interests of individuals seeking to engage in higher education. Given transparencies and efficiencies afforded by new technologies, it makes little sense to continue designing ideas about education or quality for segmented or partitioned audiences. Next-generation reports may be designed to communicate equally meaningfully to diverse stakeholders, including people who have not thought about higher education, prospective students, students, graduates, employers, teachers, and support staff. In concrete terms, this means the same data in aggregated form could flow through to academic leaders as is used to produce personalized reports for individuals.

As with advisory platforms in any area of life, next-generation reports should join what people get from higher education with what they initially invest. Platforms should articulate and align what people bring to higher education, the experiences they seek, and the success they want. Such platforms carry potential to dynamically clarify rather than compartmentalize options, experiences, and outcomes. They are unlikely to ‘solve’ all problems with buying higher education, but would likely play a direct part in improving choices, progress, and outcomes for universities, students, professions, and communities. More broadly, insights could be used by universities to improve engagement, contribution, and success of their students and graduates.

Where next?

Surely, everyone engaged in higher education wants postsecondary punters to have an intellectually engaging and personally fulfilling experience. Yet meaningful experiences, which once flowed serendipitously, must now be programmed explicitly into education designs. In a small-scale community, students and teachers naturally tend to interact. In today’s very large and digitalized tertiary institutions, which are deploying increasingly distributed forms of education, it can even be hard to know when students are flat-lining. Higher education is shifting from a highly regulated, supply-driven system to a more market-driven venture which must be increasingly sensitive to students’ needs. We must continue to explore new approaches for helping each student succeed.

Sprung from the simple proposition that there is ample opportunity to improve how people punt with higher education, this briefing has chartered the need for and nature of new reporting platforms. It looked at weaknesses in how people buy higher education, shortcomings of current quality arrangements, information needed to help students succeed, and finally the impetus for new reporting platforms. It argues that in the future higher education must be unrecognizably more transparent. There is a need to improve the nature and governance of disclosures, a need for more information, a need for a shift in focus from inputs and processes to outcomes, impact, and value or success. In short, there is a need for more effective reporting platforms.

What, then, would reflect a helpful way forward? Essentially, there appears to be value in advancing some kind of non-profit, and likely non-governmental, initiative. The need for a non-profit approach is critical to steer clear of any commercial sensitivities or conflicts of interest. A non-governmental approach is needed to engage higher education institutions and other stakeholder agencies on equal footing, recognizing, of course, that governments fund most higher education and spark many important initiatives. An appropriate series of governance, leadership, and management arrangements would need to be formed. These arrangements must be multistakeholder in nature. They must go well beyond engaging sector insiders alone and give equal power to other higher education stakeholders. The initiative will be inherently international, which is essential given higher education is marking out a new series of borderless arrangements that transcend existing agreements and dialogues. A charter with guiding principles and policies should be developed that speaks to espoused technical principles, and guides conduct of the initiative. The spark for such development will almost surely arise from conversations and debates among existing stakeholders, early adopters and advocates, though a medium- to long-term view will be required. As with the development of any new field, there is a need to define and position such interests.

Further reading for inquiring minds

This briefing was written by Hamish Coates, with earlier input from Victor Borden, Ryan Naylor and Paula Kelly.

Contributors acknowledge precursor support from the Australian Government Department of Education, and from the Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario.

Borden, V.M.H. & Coates, H. (2017). Learning analytics as a counterpart to surveys of student experience. New Directions for Higher Education.

Coates, H. (2017). The Market for Learning: Leading Transparent Higher Education. Springer.

Coates, H. (2018). Postsecondary Punters: Creating new platforms for higher education success. In: Weingarten, H., Hicks, M. & Kaufman, A. (Ed.) Beyond Enrolment: Measuring academic quality. Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Coates, H. (Ed.) (2017). Productivity in Higher Education: Research insights for universities and governments in Asia. Asian Productivity Organisation.

Coates, H., Kelly, P. & Naylor, R. (2017). Leading online education for student success. International Journal of Chinese Education, 6(1), 105-126.

Hazelkorn, E. Coates, H. & McCormick, A.C. (2018). Handbook on Quality, Performance and Accountability. Edward Elgar.

© HEFL 2025