Proving the value of tech for ed

Executive brief

- After three decades of unbridled digitalization, it is time to check what value is being created and captured for higher education, and how this can be proved and improved.

- Given that education excellence is what matters, we articulate a three-phase model to help universities evaluate quality, efficiency, and difference.

- More transparency and evidence of efficacy, especially around big money and platforms, will improve future progress.

Technologists have spruiked ‘platforms’ or ‘solutions’ to educators since the advent of ideas. In this briefing look at the educational value of such deals.

At first blush it feels cringey or even crazy to question the value of expensive technology to higher education. Not so. If all university problems are forever being ‘solved,’ why then are further platforms necessary? Why, every other year, does an emergent, genuinely amazing and existentially threatening platform/solution get swallowed instead by universities? Indeed, what evidence is there that digitalization hasn’t resulted in the conflation of education into only those facets which can be coded?

The global tech business thinks it has the whole ‘value proposition’ wrapped up, solved. Many educators beg to differ. This matters enormously, as it is educators who define, do, and in important respects, are the ‘value proposition.’

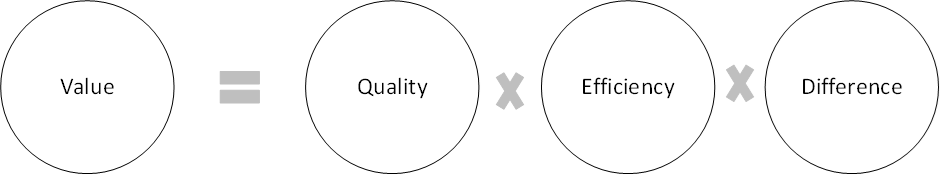

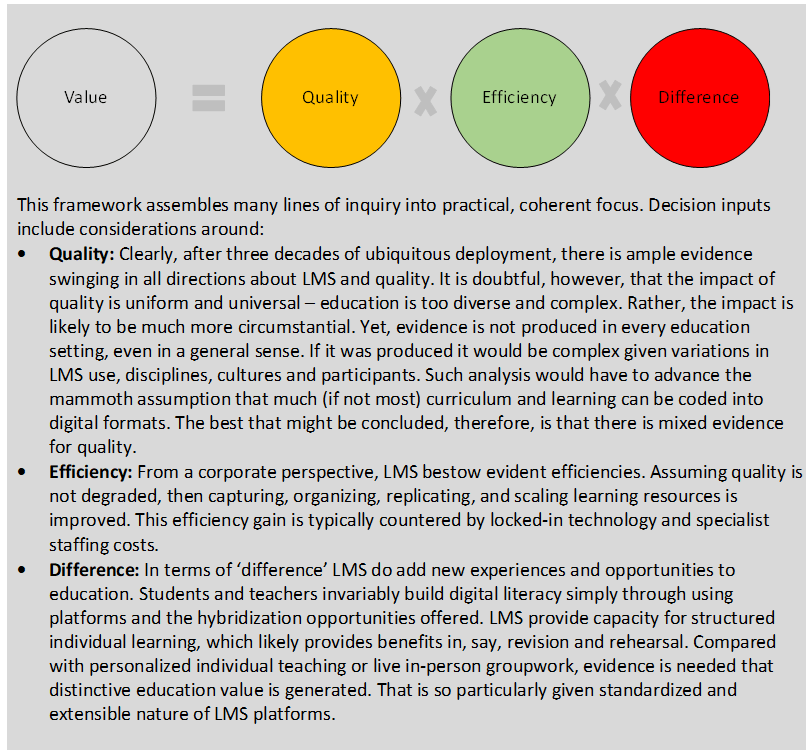

We advance a three-part framework for proving, hence improving, the value of digital technology to higher education. To yield education benefit, platforms must provide quality, efficiency, and difference.

These parameters are relevant for executive leaders, education analysts, investors, and the public. The public should care as it is usually their money on the table, and they should be shaping future of education.

Clearly, no amount of analysis is going to halt technology creation, purchase, or use. Electrons and coding are out of the gates, and away. As platforms develop, so too should the sophistication and strength of education evaluation.

Hamish Coates and Ralph Saubern

Where are you now

Socrates apparently never wrote anything down, as is often the case with today’s most prestigious education. Yet most universities today opt for far more than rhetoric or even luxury Swiss fountain pens. Instead, they delve into multimillion dollar algorithmically pulsing slices of silicone. A few decades after wide deployment of ambitiously branded ‘learning management systems,’ the rise and wobble of various forms of ‘online,’ and growth of ‘artificial’ and ‘edtech,’ it is very reasonable to ask if it’s worth it, if it is for who, or at the very minimum, to ask how anyone could tell.

Technologists have spruiked ‘platforms’ or ‘solutions’ to educators since the advent of ideas. In this briefing we advance an important mechanism for establishing the educational value of such deals. After clarifying contemporary dynamics shaping the awkward dance between software education, we articulate a three-part framework for determining education value, and explore its application in four areas. We argue that more robust evidence of efficacy will improve future digitalization.

At first blush it feels cringey or even crazy to question the value of expensive technology to higher education. Tech conferences hum and swing as millions network, enthuse about change, and foster collaborations. We have written dozens of books and papers on all kinds of tech, and even built platforms. We recognize the audience for critiques like that mooted here is much more refined. So much talking, coding, downloading, investing, and presenting has been had. So much valuing, including by wise experts, has already been done.

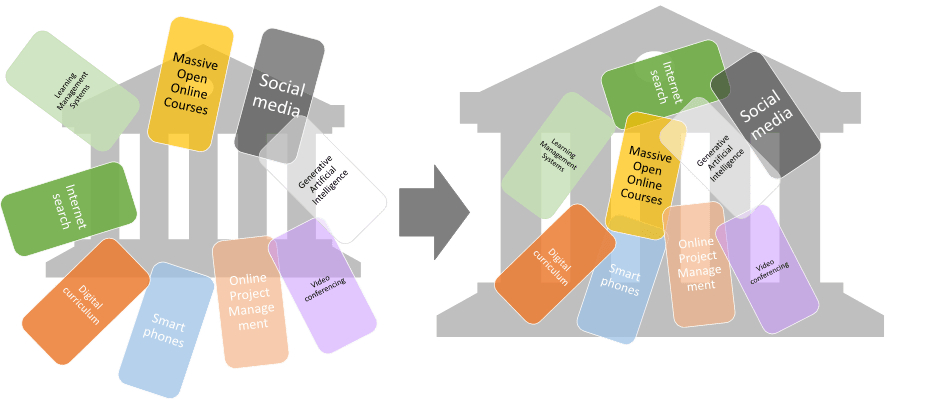

Thinking just a moment longer, however, affirms at least a slither of value undergirding such inquiry. With such angst and uncertainty scattered around higher education, it is fanciful to insist that all is made good by a fondant of tech. If all university problems are ‘solved,’ why then are further platforms necessary? Why, every other year, does an emergent, genuinely amazing and existentially threatening platform/solution get swallowed instead by universities (Figure 1)? The world of higher education has certainly ‘re-humanized’ after recent pandemic distancing, signaling limits in the tech promise. Beyond smart marketing and attractive images, what evidence is there of improved learning? Indeed, what evidence is there that digitalization hasn’t resulted in the conflation of education into only those facets which can be coded? In the name of ‘education innovation’ have algorithms actually spurred transformation, or entrenched unproductive practice? Even, and perhaps especially, for tech there is value in opening core questions to inquiry.

Figure 1: Universities gobble threatening software

How can the value of digital learning technology to higher education be proven, and improved? The global tech business thinks it has the whole ‘value proposition’ wrapped up, solved. Many educators beg to differ. This matters enormously, as it is educators who define, do, and in important respects are the ‘value proposition.’ Education technology has quite evidently furnished many enhancements in administration and ‘delivery.’ Curiously, however, it remains difficult to attest with certainty whether edtech has improved education itself.

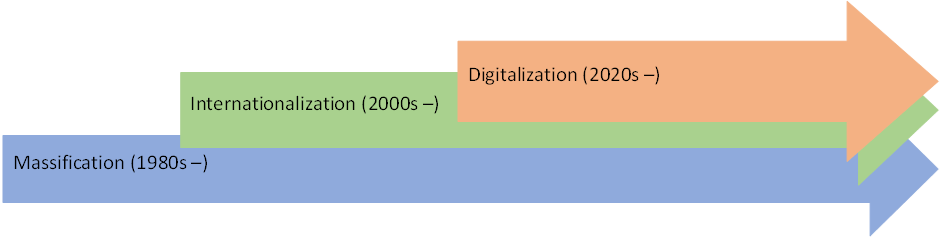

The digital transformation of higher education is now a mainstream topic, and a serious and prudent dialogue for higher education. It is not one which is odd-ball, cynical, or glorified by technozealot hype. Indeed, building on prior eras of massification and internationalization, it is not too courageous to conjecture that digitization may be the major driving and even transformational force (Figure 2). Penetration has unfolded in step with Amara’s law, which refers to overestimating technology’s short-term effects but underestimating its long-run impact. In the first two decades of the internet, education technology tended to be led by engineers and managers who understandably focused on technological fundamentals and innovations rather than broader educational and institutional returns. The decades ahead look different. Education and technology will be more closely integrated. Rather than focusing on technology, contemporary academic leaders have begun to lever different platforms and expertise that enable productive education, and as we unpack below, sometimes in previously unexpected ways. Education and business leaders have seized this change and built substantial global education service corporations which are of major relevance to higher education. Venture capital investment in digital platforms has soared to record heights, inspiring new entrants and further growth, and merger and acquisition activity among sector winners.

Figure 2: Higher education transformation eras

Framing education’s techno dance

Obviously, such broad inquiry could be approached in myriad ways. We situate our direction by standing back and needling open points of interconnection between education and digital technology (Figure 3). This infuses important texture in the matter to hand, opening space for the analysis which follows.

Figure 3: Fr/agile developments

We must acknowledge huge and entwined engagement. Seemingly every university has an SMS, LMS and CMS, plus more. The scale of software investment has been magnificent, many hundreds of billions. This is of course only part of the equation given additional customization, implementation and innovation. Complex education systems are rarely purchased straight off the shelf. Thousands of learning scientists, developers and support staff are employed, spurring ongoing flows of cash and expertise. Money is important, but far from the most important facet of education.It signals value, but it is not as valuable as learning and innovation.

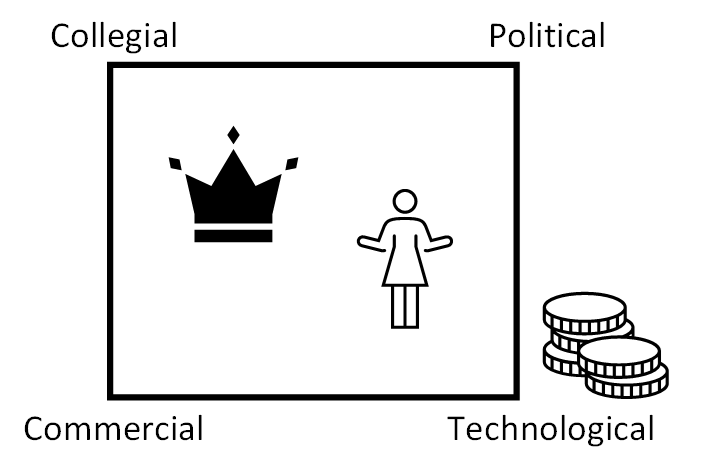

The scale of engagement stimulates questions of an ‘ontological’ or ‘operational’ nature, if not of an existential nature – these questions run deeper than strategy. In the 1980s Burton Clark famously distinguished three forces shaping higher education. His ideas have been deployed to examine how universities, systems and even people in the sector are positioned within a triangle of academic/collegial, state/political, and market/commercial power. Does digital technology forge a fourth vertex? Is the medium that influential? Or does it transform any or all of the existing three forces? This kind of questioning is not obtuse. It forces consideration of whether platforms, especially large enterprise systems, carry efficiency, quality, or even broader transformative power and potential.

The scale and penetration of education technology raises serious questions about governance. Understanding tech is pivotal to governing universities if it holds that algorithms and system settings control learning and teaching, determine how students and teachers interact, and shape the character of teaching resources and student work. It could be argued either that understanding education procedures, or keeping suitable distance from practical matters, have long underpinned effective governance. But pervasiveness and particularity of contemporary platforms prompt novel concerns. There is value in efficiency improvements which remove waste and bad practice, but governors must be able to discern when standardization tips into conflation, which makes their own institution the same as many or even most others. Academic learning, even in tightly accredited fields, means intellectual play with ideas.

These points prise open deliberation of precarious interplays between platforms and academic work. As the Socratic reference makes clear, it is a deliberate decision to code education into the binary logic of digital technology (Figure 4), such that everything – and potentially every university – converges on sameness. Strange as it may appear, just two decades ago digitalization of learning, and loading resources on enterprise platforms (i.e., PPT on LMS), were controversial with faculty and even leaders. Recording or broadcasting live lectures was fraught, not least if it surfaced substandard or inappropriate practice, but also genuinely exposed sensitive and delicate learning interactions. Dangers can arise when eager coders bust through complex deliberations around education. The recent eruption of generative artificial intelligence poses substantial questions for production of learning resources, and authenticating student assessment. Teachers may struggle to produce great assessment designs, and students may struggle to respond to them, but at least they gave it a go.

Figure 4: Digital logic for education

These considerations are just the tip of any decent problematization of how education dances with technology, though sufficient to reveal a sprinkling of issues in play. Universities have not been disrupted – destroyed and rebuilt – by digitalization despite decades of hyperbole and prognostication. That said though, changes have been non-trivial, far from transparent or resolved, and idiosyncratic.Commercially interested sales pitches are likely insufficient for establishing value, and even these scratch for substance to underpin invariably superficial technozealous rhetoric.

Skewers in the fire

How can the value of digital technology to higher education be proven, and improved? We advance a three-part framework. Figure 5 summarizes the three dimensions which construct the framework. It is underpinned by myriad complex and well-trodden ideas on learning, assessment, productivity, quality, value, and management. There is no shortage of frameworks for evaluating the value of education technology, ranging from those evoked by commercial players, by university managers, and by educators themselves. The lens extended here is straightforward and educationally established. Commercial analysts are adroit at poking around financial valuations, which are important, but it is education, after all, that edtech is all about.

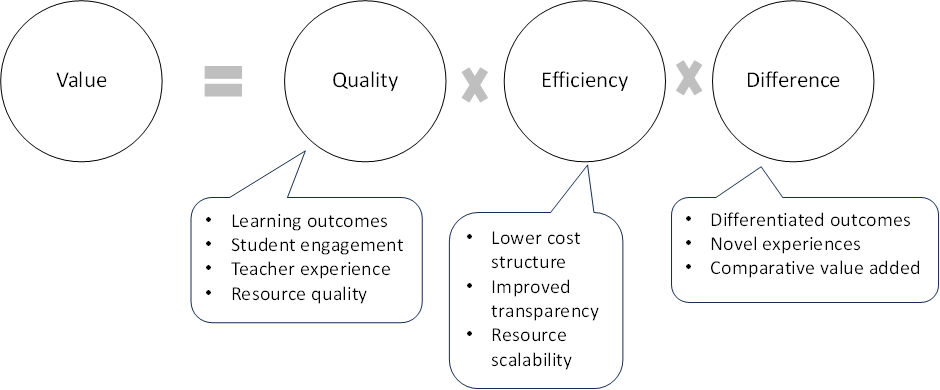

Quality is up the top. While obviously a complex topic in higher education, on face value there is not much to be said for adopting any technology which reduces quality. An argument could be raised for efficiency and scale (considered in the next section), but even so, minimum quality standards apply. Herein lies a complexity, for as noted above the digitalization of higher education may well transform core characteristics of the materials and practices in play. As the following analyses convey, beyond realizing basic standards, independent evaluation of major education ingredients – resources, teaching, support, and learning – is likely required. Many of these ingredients can be conceptually, practically and scientifically spongey, placing a premium on hard data, particularly for the quality of student learning.

The second dimension, efficiency, is influential in a variety of ways, from lower costs to improved scalability. Efficiency is nice, but neither necessary nor sufficient to spur an embrace of education technology. Education may well be digitalized in costly ways with an eye to making available an experience such as a simulation. Tech may be sought to render a process more efficient, yet may degrade quality in unacceptable ways that hinder implementation. Generally, efficiency is a desirable quality; there is little value in developing or deploying technology in ways which raise costs for institutions or stakeholders.Third, does the technology make a difference? Does it add new dimensions to student learning? Does it transform how teachers teach? Does it transform how students learn? Looking beyond productivity vectors (quality and efficiency), does the platform or system add new experiences and opportunities to education? This signals a search for distinctive value adds which is reasonable given promises and offers often ventured by platform vendors.

Figure 5: Education technology evaluation framework

Proving it’s alright for learning

These three dimensions are straightforward and relatively uncontroversial. Combined, they help unpack four takes on the educational value of technology to universities.Executive leaders who make procurement decisions need decision support. Even before commercial due diligence, does the platform make education sense? Does it boost productivity and make a difference? The rise of digital native leaders means there are more people in executive roles who can apply their knowledge and practice sets to these all-important questions. But tech has matured and infiltrated education and thorny situations remain. Given the stakes, it is reasonable to demand strong evidence of education value. This raises the bar on evidence of education quality.

Figure 6: Executive leader analysis blueprint

Just outside the C-suite lie deeper concerns about productivity. Productivity implies quality maintenance or improvement, which differentiates it from efficiency. Digital platforms may be shown to enhance efficiency through cost reduction, operational simplification, risk mitigation, or process control. But what about the quality of teaching and learning? What evidence is there that education has improved? The Gartner Hype Cycle implies that technology lifts the productivity plateau. Results will vary for different kinds of platforms. Has this been confirmed over time for specific ‘solutions’?

Learning Management Systems are a case in point. For nearly three decades LMS firms have promoted platforms with claims that they improve efficiency, expand access, provide management information, support users, and enrich learning. Given the stakes and investment, it is imperative to step back from smooth marketing rhetoric and clarify value. Figure 7 presents a summary of the decision support framework for executive leaders.Assuming education value – quality, efficiency, and difference – is ascertained, what options are there for sharing the spoils? The tech industry presents higher education with an interesting conundrum. Universities are accustomed to their standing as large prestigious players, backed by governments, talent, and tradition. Yet just the top two United States tech firms match total revenue estimates of all that country’s universities. While no longer the big kid on the block, a university’s nature and standing substantially influences relations formed with other firms. Universities with strong market power should be able strike more value-sharing deals than universities with fewer reputational or intellectual resources. Even so, when an education technology company is acquired for many billions of dollars, clearly this money comes from somewhere. There is intense global debate about privatizing publicly funded research and the need for open publishing. No such debate yet about education.

Figure 7: Case study – LMS value reckoning

There is value in public disclosure of the ideas birthed above. Vendor research exists in many cases, but while informative it is obviously conflicted. Commercial intelligence platforms exist, as do advocates, and local or large-scale platform/education evaluations. But there is a large (indeed huge) gap between sources of information. What evidence about edtech platforms is generalizable and trustworthy, such that we confidently say which platforms make a difference to education and learning? Thousands of super-smart people make software applications to “solve” higher education, often independent to the more than 130,000 university “teachers” in Australia alone. There must be a gateway to trusted information. The Australian pharmaceutical benefits scheme (PBS) does just this: lists which globally produced drugs are eligible for government subsidy. Why not the same for education: a list of approved platforms with proven education efficacy. The Australia Government has recently and belatedly moved to regulate social media for people under 16 – the larger value-creation question remains for education in general. Beyond finance and digitalization, what standards apply to determine whether technology makes a difference to people’s learning and development?

Analog for education

After three decades of unbridled spending on digital technology, it is time to check what value is being created and captured. Has widespread digitalization of higher education made any difference, and for who?

Digital transformation of higher education is happening in many ways, and all at once. It is no longer an isolated vertical or enabling contributor, but rather something threaded throughout or sprinkled across all education activities. This circumstance presents complex and urgent imperatives for people involved in university education who generally lack deep expertise in understanding and navigating emerging education technologies. This is far from a call to all university leaders, teachers, and students to down tools on the day job and cram to become pseudo tech experts. This misses the point. Education is what matters, and technology is an important but fluid and contributing enabler. As with understanding many transformations and disruptions, therefore, success hinges on reviewing fundamentals, taking stock of options, and agreeing on how to optimize outcomes. Fundamentally, education is an interplay between a teacher and a learner talking together about knowledge and skills. As education gets larger and more complex, there is a need for different forms of mediation. This demands education nous to register success via the quality of engagement and learning. Acquiring at least at a superficial or minimal understanding of the platform and financial ecosystems of contemporary technology is essential for people working in and around higher education. Taking the time to reflect on genuine education innovation is more important.

Clearly, no amount of analysis is going to halt technology creation, purchase, or use. Electrons and coding are out of the gates, and away. As platforms develop, so too should sophistication and strength of education evaluation. It is time to ask not just “which system.” We must also ask “whether system or not.” This demands more evidence, most particularly of learning quality, and of learning difference. Is the binarization of higher education the way to go? What is left as a residual? What, importantly, must be protected, to keep humanity in play? As Pablo Picasso is quoted as saying, “Computers are useless. They can only give you answers.” There is much more to universities than this.Stirring dialogue around technology almost inevitably provokes interest in more transparency. Digitalization of higher education undoubtedly moves universities in a commercial direction, not least as the smallest teaching interactions are sewn into proprietary platforms owned by big global capital. The last twenty years have spawned opportunities for an influx of and often private finance. This has fuelled, and in important respects transformed, core facets of higher education. This business involves huge interests, thousands of super-smart people, thorny politics, and tonnes of secrecy. Not much is written, and in certain cases even known, about these matters. Perhaps this is due to lack of analytical expertise, to company allegiances, to commercial sensitivities. Perhaps it is due to the fraught optics of public universities outsourcing core academic work. But it is important to know about, and in particular in educationally meaningful ways.

Further reading for inquiring minds

Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (AISTL) (2023,4). Evaluating the evidence for educational technology: Part 1 – the technologies; Part 2 – enabling learning. Accessed from: https://www.aitsl.edu.au/research/spotlights

Beaton, J., Xi, G. & Coates, H. (2022). The digitalisation of higher education: The transformative role of EdTech. In: Dee, J.R. & Leisyte, L. (Eds.) Research Handbook on the Transformation of Higher Education. Cheltenham, Edward Elgar.

Coates, H. (2006). Student Engagement in Campus-based and Online Education: University connections. London: Routledge.

Coates, H. (2017). The Market for Learning: Leading transparent higher education. Dordrecht: Springer.

Coates, H. (2020). Higher Education Design: Big deal partnerships, technologies and capabilities. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan.

Coates, H., Liu, L. & Zhang, J. (2023). Online Assessment Platforms. In: Wa-Mbaleka, S., Thompson, K. & Casimiro, L. (Eds). The SAGE Handbook of Online Higher Education. Thousand Oaks: SAGE.

Coates, H., Liu, L. Zhang, J., Jiang, F., Zhang, D. & Godinho, S. (2021). Next-generation assessment spurs smarter learning. Journal of Supranational Policies of Education, 13, 88-103.

Coates, H., Xie, Z. & Hong, X. (2020). Engaging transformed fundamentals to design global hybrid higher education. Studies in Higher Education.

Coates, H., Zhang, Y., Li, M. & Zhong, Z. (2022). A Turning Point for Chinese Higher Education: The development of hybrid education. London: Routledge.

Saubern, R. (2022). EdTech in the service of learning: The importance of evaluating education technology. Accessed from: https://www.acer.org/au/discover/article/edtech-in-the-service-of-learning-the-importance-of-evaluating-education-technology

Saubern, R., Taylor-Guy, P., & van der Keij, F. (2022). Introducing the Education Technology Value Evaluation Tool for Schools. 2022 International Conference on Assessment and Learning (ICAL), 1–6.

The authors offer profound thanks to four expert anonymous reviewers for superb feedback.

© HEFL 2024