Using next-generation assessment

Executive brief

- As higher learning becomes more valuable and widespread it is essential to innovate assessment to ensure integrity, authenticity and productivity.

- Next-generation assessment reform has produced smarter forms of learning.

- Next-generation learning is education-led by people, deploying technology and process improvement to improve experiences and outcomes.

As demand grows, interest in learning has grown well beyond class-based interactions between teachers and students. Assessment plays a huge role in learning. Done well, assessment plays a core role in articulating what learners already know, in helping people learn, and in spotlighting what learners need to learn.

Here lies a problem, for despite the crucial role it plays in higher education, much assessment is still being done today as it was a century ago, despite multiple growing reasons to reform. Technology is one tool, not the brains, for making progress.

Learning is smarter when next-generation assessment is reformed in ways that enhance integrity and productivity. Next-generation assessment reform means pushing beyond traditional assessment which is costly and fragile when scaled.

Spurring next-generation assessment rests on education-led design, robust platforms, and careful reconfiguration of management and business processes. Core areas for change include making tasks, managing administrations, implementing and proctoring, and marking and reporting.

Three developments spur such transformation:

- Evaluation, diagnosis and re-design,

- Engaging with smart platforms, and

- Collaboration and scaling.

Recent years have marked an inflection point when assessment has become harder for universities than for students. Research has affirmed the value of education-informed assessment reform.

Hamish Coates

Improving learning

Interest in learning has grown well beyond class-based interactions between teachers and students. Global population growth keeps spurring an increasing need for higher education to reach more people than ever before. Economic development is shifting more people in more countries into professional roles which require higher learning. Longer lifespans are leading people to work for longer, requiring re-skilling, re-directing, and re-certification. The global race for top-talent has intensified, spurring a need to understand not just learning at scale but also in extremely novel contexts. New technologies are putting existential pressure on traditional forms of practice.

Assessment plays a huge role in learning. Done well, assessment plays a core role in articulating what learners already know, in helping people learn, and in spotlighting what learners need to learn. Done poorly or without reflection, assessment can waste time and money, spur anxiety and distaste for learning, provide misleading information, and generate adverse outcomes. Assessment reform seeks to shift practice hence learning towards the positive end of this spectrum. Reformed assessment gives people the feedback and encouragement they need to learn in smarter ways.

Here lies a problem, for despite the crucial role it plays in higher education, assessment has yet to have its transformational moment. Online learning and workforce changes have transformed curriculum and teaching. Major platforms and business transformations have disrupted and reconfigured admissions and broader forms of student management. Yet much assessment is still being done today as it was a century ago, despite multiple growing reasons to reform.

This briefing spotlights reforms required to achieve underpinning ‘next-generation’ forms of assessment, and articulates feasible steps ahead. The briefing outlines smarter learning, highlights next-generation assessment reform, delves into core change areas, sketches stages of reform, and concludes by articulating helpful steps ahead.

Smarter learning

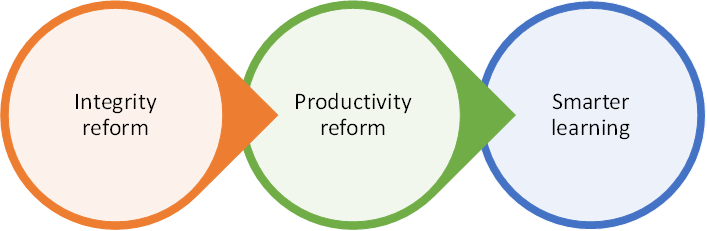

‘Smarter learning’ is the idea that ‘learning is smarter’ when next-generation assessment is reformed in ways that enhance integrity and productivity. This means going beyond incremental change in faculty practice, beyond tinkering with platform settings, and well beyond using smart language.

Figure 1: Smarter learning

The integrity of assessment is driven by a range of technical criteria. Gleaned from a century of measurement science research, such criteria ultimately go to spotlighting and emphasising different forms of validity. It is important that consideration be given to each important criteria (Figure 2) in task design, development, implementation and review. The quest is not that a task be flawless, but that it has known and optimised properties.

Figure 2: Indicative assessment standards with prompt questions

| Standards | Prompt questions |

| Coverage | Does the task cover sufficient range and depth of content and all relevant material? |

| Authenticity | Does the task seem relevant and real? Does it appear useful and meaningful? |

| Criterion | Does the task correlate with other indicators of similar topics? |

| Discrimination | Does the task distinguish varying performance levels? |

| Practicality | Is it easy for students to engage with the task? Is the task ‘user friendly’? |

| Efficiency | Is the task efficient to implement and use standard equipment and procedures? |

| Responsiveness | Does the task yield timely feedback for students? Does it support lively learning? |

| Interpretability | Are task requirements understood by all students? Is task language easy to read? |

| Transparency | Are task requirements and expectations clear to students? |

| Educational | Does the task prompt students to learn and contribute seamlessly to the experience? |

| Consequential | Does feedback have expected consequences and promote improvement? |

| Production | Are tasks produced to a high standard? Have they been designed and proofed? |

| Clearance | Have relevant legal and cultural approvals have been secured for the task? |

| Consistency | Does the task perform consistently across people, time and contexts? |

| Alignment | Does the task align with students, curriculum, teaching and outcomes? |

| Distinctiveness | Is the task sufficiently distinctive and does it add unique value and insights? |

| Scoring | Do rubrics enable sound and generalisable scoring? |

| Validation | Have task materials been validated and improved by students? |

What does it mean to make assessment more productive – to make quality-informed advances in efficiency? Enhancing the productivity of assessment goes in general terms to increasing the ratio of outcomes to inputs by delivering the same or more outcomes for the same or fewer inputs, while holding quality constant. Outcomes, in this respect, include the number and variety of assessments. Inputs include staff and student time as well as direct and indirect costs. Boosting assessment productivity is likely to be achieved through input reduction. This necessitates a different production function, ideally in which assessment is woven into an engaging student experience.

Smarter learning enables, enriches and augments traditional collegial practices. It does not impose top-down reform, which rarely resonates with everyday academic practice. It strengthens academic practice. This differentiates it from existing or prior governmental or commercial initiatives.

Next-generation assessment reform

Achieving smarter learning hinges on next-generation assessment reform. This means overhauling traditional approaches to bring about more robust and productive solutions. Three general models help frame change.

Assessment reform can be framed in three eras (Figure 3). Traditional approaches are highly individual and collegial in nature. These legacy practices have been stretched and patched for bigger delivery as higher education has expanded. Traditional assessment is costly when scaled, and quality suffers, often the breaking point. Much of this growth has been expansionary rather than transformative in nature. Shifting to next-generation assessment, by definition and design, represents the kind of reformed assessment which carries potential to undergird ‘smarter’ forms of learning.

Figure 3: Three eras of assessment

| Traditional | Stretched | Next-generation | |

| Timeframe | 1990s and before… | 1990s to 2020 | …2020s and after |

| Authority | University | University or regulator | Shared |

| Production | Solo academics | Academic teams | Co-creation |

| Format | Paper | Paper and online | Online |

| Location | Campus | Campus and online | Online |

| Implementation | Universities | Universities | Engineers |

| Scoring | Solo academics | Moderated practice | Automated |

| Reporting | Generic | Contextualised | Customised |

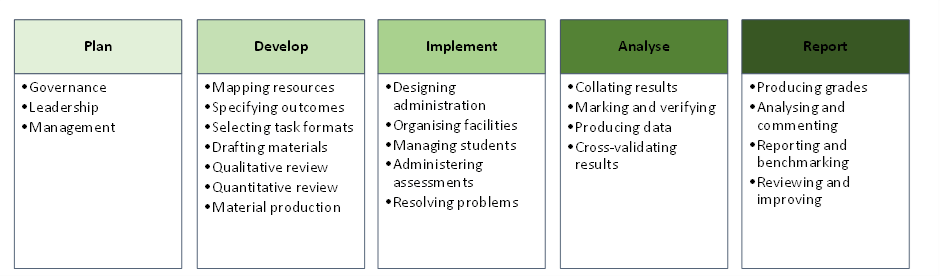

Figure 4 presents a model to help spotlight areas for change. This brings together value chain and measurement science perspectives into a lens for surfacing bottlenecks and options for reform. The model has been validated in several large-scale studies as a means for precipitating next-generation assessment.

Figure 4: Assessment phases and activities

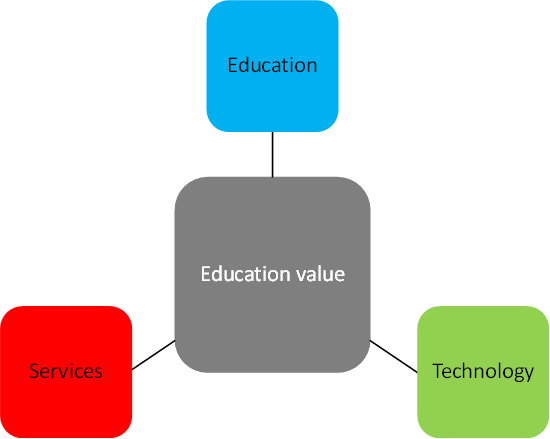

Ultimately, spurring next-generation assessment rests on deft education design, robust platforms and careful reconfiguration of management and business processes. Figure 5 depicts this ‘value-creating constellation’ in which practical nous is the glue that binds these ingredients in ways which yield additional quality and productivity:

- Education expertise furnishes theories and ideas but not the resources or infrastructure for change. Successful contemporary reforms put education first and position technology and operational support as enablers.

- Technology is an ingredient which serves well in facilitating and catalysing roles, Despite compelling rhetoric, contemporary academic reforms have flourished not because they involve technology, but because they engage technology in practical solutions which advance the productivity of higher learning.

- Service reform is essential, including to financial and operating protocols, to avoid inadequate, unstable and precarious change.

Figure 5: Value-creating constellation

Delving into change

Making assessment hence learning improve rests on four distinct phases. These include (Figure 6) making tasks, managing administrations, implementing and proctoring, and marking and reporting.

Figure 6: Steps to make learning change

From a functional perspective, making assessment tasks involves creating, validating, aligning and optimizing online or paper-based tasks. Academics have been making assessment tasks forever, though in traditional ways and not necessarily in ways which optimise educational, practical or technological resources. Shifting away from individual or ad hoc task development and adopting task authoring tools boosts the integrity, efficiency and quality of assessment. Such tools enable the adoption of richer and dynamic tasks, collaborative task development, task sharing, and more sophisticated mapping to education and vocation competencies. Deploying such tools helps to create and edit tasks, integrate scattered resources, tag and map tasks, align assessment with learning outcomes, proof materials, and generate hybrid assignments and exams.

Managing assessment administrations is about scheduling people, infrastructure and resources. While all higher education institutions have existing arrangements for handling this, these are typically configured in ways which suit traditional rather than next-generation assessment. For instance, they may process programs, courses or people in batches to undertake static tasks, whereas much more dynamic and nuanced forms of sampling can be deployed to enable more astute and authentic matching of students to tasks. Dedicated scheduling software can also help institutions and learners reduce assessment risks and costs by managing schedules, rostering staff and absences, coordinating paper delivery and third-party logistics, logging and investigating incidents, and handling special needs and situations.

Next-generation assessment entails implementation reform, and to the extent required, changes to proctoring arrangements. Particularly when linked with more intentional assessment design, step-change improvements in delivery and security become feasible. In general, this involves deploying technologies which assure quality implementation. Integral services involve planning assessments, registering and verifying students, delivering automated and coordinated communications, allocating and aligning people and venues, delivering practice, scheduled and on-demand assessments, enabling real-time monitoring and authentication, and reporting performance metrics. The adoption of contemporary implementation platforms helps shift beyond batch processing of students and assessments, enabling much finer-grained and even task/competence-level alignment of students with assessments.

Marking and reporting is the final cluster of assessment phases and activities. Typically, these activities are handled by academics working alone or in small teams, with reporting taking place as a somewhat private activity between teachers and students. Confidentialities around reporting must be protected, but there are quality and efficiency limitations with keeping all aspects of this process secret. As most large-scale assessments signpost, huge quality dividends can be derived from collaborative marking and from sufficiently anonymised benchmarking. Well-managed collaboration can increase the reliability and efficiency of marking, and reduce reporting errors and delay. Platforms have ample means of supporting secure marking, automating marking, managing markers, dealing with response validation, and generating benchmark and competence-level reports.

Developing transformation

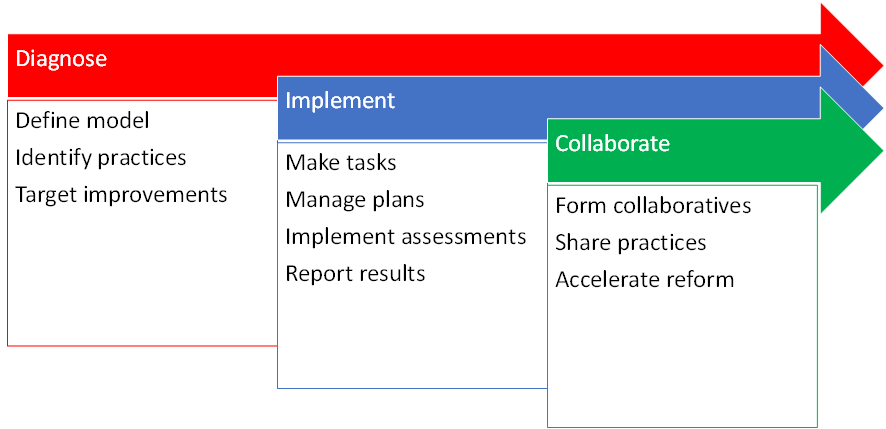

If such aspirations and advance have merit, what changes are required to spur these forms of assessment reform hence development of smarter learning? Three developments work together to spur transformation (Figure 7), affirmed in several studies.

Figure 7: Stagewise transformation steps

First, there is a need to evaluate, diagnose and re-design prevailing assessment arrangements. This is complex, as assessment practice is usually spread across myriad platforms, people, computers, files and perspectives. To gain insight, it is important to step outside invariably complex and messy circumstances, apply a broader model, and spotlight areas for reform. Thinking differently about assessment, giving consideration of methodological, technological and practical factors, sparks consideration of the redesign that underpins next-generation assessment.

Second, there is a need for teachers, institutions and students to engage with sufficiently sophisticated assessment platforms. This of course involves all of the issues associated with new technology adoption, as well as being made more complex given academic and workforce sensitivities around assessment and entrenched institutional practices. A fertile way forward, beyond system-level deployment, is to enable faculty to play around with systems and experience their potential.

Third, the activation of localised solutions is a precondition for realising perhaps the broadest value of assessment reform, being the formation of academic collaboratives. The modular nature next-generation assessment means that such individual experimentation can be joined-up into a synchronised network. These, in many respects, mirror the collaborative networks which sustain and advance academic research. Such collaborations can be woven together across institutional and disciplinary boundaries.

Beyond the tipping point

These are interesting ideas, but also ideas which have been proven. These reform options have already been tested in hundreds of higher education contexts. Research has affirmed the value of education-informed assessment reform in terms of improvements to quality and productivity. Rough estimation conveys that about nine billion pieces of assessment are conducted in higher education each year, with about one billion being done online. Given that not all online assessment will be optimised, there is ample scope for growth.

Recent years have marked an inflection point when assessment has become harder for universities than for students. Every day, hundreds of millions of people in the world’s 20,000-plus institutions engage in unproductive assessment of learning. This costs time and money, hinders learning, and squanders the capacity for higher education to prove its social, economic and professional contribution. This briefing articulates how smarter learning spurs next-generation assessment. Smarter learning makes possible step-change advance which enhances the sustainability and prosperity of higher education.

Such change is required given the growth of higher education alone. Recent reckoning in Australia found that that the number of pieces of assessment each year had risen from around seven to nearly 30 million in the last twenty years. With no change in production function this implies a quadrupling in recurrent annual costs to more than AU$400 million for marking alone, leaving aside other large costs for assessment development, administrative and support staff, capital and intermediaries. All up, including indirect costs, it is easy to see how largely unreformed assessment practices might be costing close to a billion dollars annually. Given that Australia has less than half a per cent of the world’s higher education students, these figures balloon into a much broader need for assessment productivity reform.

Further reading for inquiring minds

Cantwell, B. Coates, H. & King, R. (Eds.) (2018). Handbook on the Politics of Higher Education. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Coates, H. & Richardson, S. (2012). An international assessment of bachelor degree graduates’ learning outcomes. Higher Education Management and Policy, 23(3), 51-69.

Coates, H. (2016). Assessing student learning outcomes internationally: Insights and frontiers. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education 41(5), 662-676.

Coates, H. (2017). The Market for Learning: Leading transparent higher education. Dordrecht: Springer.

Coates, H. (2018). Next Generation Assessment. Melbourne: Online Education Services.

Coates, H. (2020). Higher Education Design: Big deal partnerships, technologies and capabilities. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan.

Coates, H. (Ed.) (2014). Higher Education Learning Outcomes Assessment. Frankfurt: Peter Lang.

Genix Ventures (2021). Examina+. Accessed from: https://examinaplus.com.

Hazelkorn, E., Coates, H. & McCormick, A. (Eds.) (2018). Research Handbook on Quality, Performance and Accountability in Higher Education. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.