Renovating higher education information for 2050

Executive brief

- It is time to make evidence for valuing future university education.

- Current metrics are withering in relevance, specificity and impact, providing weak insight for universities, government, and the public.

- Universities will thrive with fresh information about opportunity, partnership, co-creation, resource use, integrity, and economic returns

To spur and accelerate Australia’s higher education transformation, it is imperative to innovate the nation’s higher education information architecture. Current metrics, designed 25 years ago with elitist and colonial assumptions, are withering in relevance and impact. The sector is not even grasping easily reachable possibilities. Australia, once innovator, now lags.

Now is the time to embrace broader forms of education value. This means moving well beyond student satisfaction and engagement information. New metrics make new language, new stories, and new differences. This is what universities are about.

A revamped and reconfigured information architecture will equip policy makers and university leaders to make informed decisions, develop improvement roadmaps, and drive social value.

Imagine working with instructive, meaningful insights into opportunities, partnerships, co-creation, and education returns. Students, universities and communities all win with such information. Connections will be more informed, productive, and engaged. It is timely to be intellectually venturous. It is time to advance value for the decades to come.

Hamish Coates, Angel Calderon

Happy, engaged, and contributing

New metrics make new language, new stories, and new differences. This is what universities are about. Imagine working with instructive, meaningful insights into:

- Learning opportunities, revealing whether faculties, institutions, and systems deploy learner- or learning-centric systems for opening opportunities;

- Academic partnerships, especially digital partnerships and hybrid learning spaces;

- Resource use in education services, as opposed to research, works, or operations;

- Resilience, and to what extent universities have the capacity and capability to understand and help each student;

- Situated resources – whether institutions are furnishing curriculum accessible to non-traditional students and for those who most need them;

- Teachers and teaching, and in particular how well academic integrity is sustained, and how well it is protected in teaching innovations;

- Social co-creation – whether an institution is reaching beyond its walls into the lives of a much broader, potentially global, population and its abundant, diverse communities;

- Education returns, including solid data on financial and knowledge returns for individuals and communities; and

- Academic value, including articulating and validating learning success.

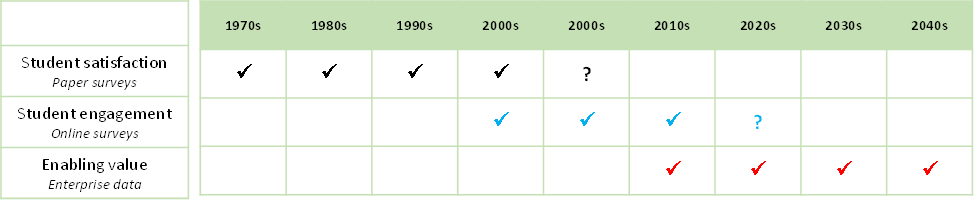

It is imperative to innovate Australia’s higher education information architecture to spur and sustain sector transformation. Current metrics designed 25 years ago are withering in relevance and impact. The sector is not even grasping easily reachable possibilities. As Figure 1 conveys, now is the time to embrace significant practices regarding broader forms of education contribution. This means moving well beyond student satisfaction and engagement information. It is timely to be intellectually venturous. It is time to advance, without historical or sentimental constraint, qualities of value for the decades to come.

Figure 1: Higher education data across the decades

Student satisfaction measures boomed years ago. More than thirty years ago, universities grew beyond an era when most people might have known each other by name, and it became necessary to produce more meaningful and objective information about education. Student satisfaction statistics garnished with scholarly rhetoric were spread entrepreneurially throughout the English-speaking world. Powerful new information on student engagement was advocated by United States experts, growing into one of the sector’s largest information regimes. Australia leveraged these developments to implement then-innovative information on students’ engagement with effective education experiences. This data became sector-wide, institutionalised, then nationalised. This data regime centered on enrolled learners, replacing one developed decades earlier focused on graduates.

Metrics lose their distinctiveness and edge when absorbed into large systems of academic review and governance. They wane as they age. Their power is hobbled. Much education information swirling around Australian higher education today, like that publicly reported and factored into provider regulatory reports, was designed 20-25 years ago in response to very different educational and institutional arrangements. It was based on elite-era and colonial assumptions, snail-mail logic, and forms of university leadership very different to today. It is timely to make go beyond last century’s frontiers. It is time to promulgate information relevant to understanding and leading future university education. Learners would be really satisfied and engaged if academics and university leaders acted on such information to forge opportunities relevant to them.

Changing situations, ideas, and practices

Higher education in Australia keeps changing in non-linear ways. Politically, the sector keeps moving from a hyper-global commercial position to a more nationally and regionally focused, statist position. The academic knowledge once considered gated and prized has become digitalized, much teaching coded and commoditized, and assessment increasingly automated. Student numbers have ballooned, and learner cohorts have exploded, yielding much greater support needs, different forms of social interaction, and changed expectations.

As universities change, so too must the information on which their leadership relies. The sector needs to renovate its data and evidence architecture. Information yields diminishing marginal returns unless it keeps evolving, unless it helps explain and respond to change. Results cease to razzle-dazzle and have impact. In the inevitable dialectic of system governance, institutions learn how to game the data rather than quiz and action the data. Indeed, once thriving and world-leading, current education statistics in Australia have wilted and drifted. The data is far less relevant to government and institutions. This is dangerous. It means plans and programs are forged on the anvil of spurious targets, that quality practice is ignored, that we reward people and institutions in distorted ways, and that changes are made which waste resources and diminish value.

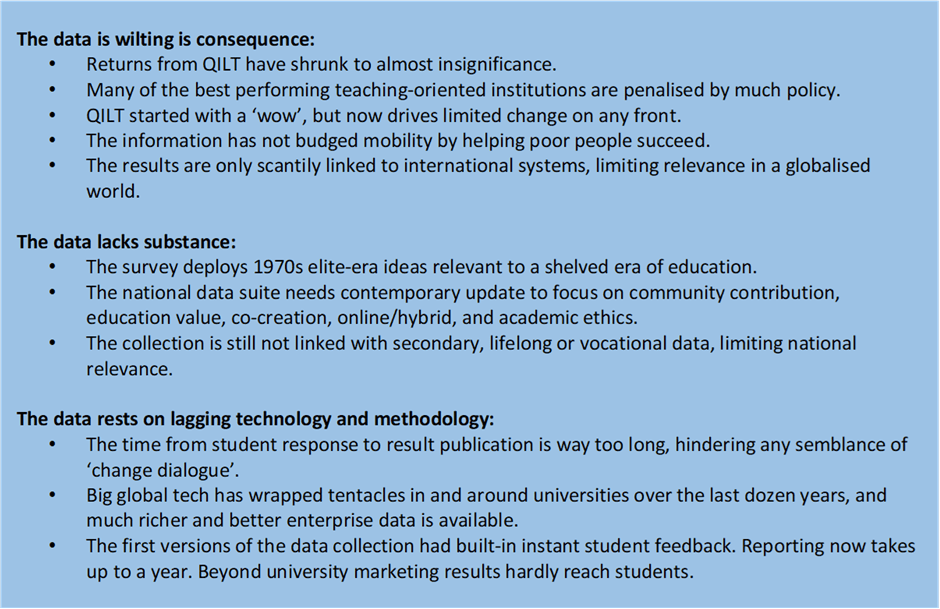

Figure 2 presents a case study of the need to redo the prevailing student quality data in Australian higher education. The case provides practical, substantive and technical snapshots as to why Australia’s domestic prevailing data system QILT is wilting and needs a major refresh. It is time to recycle, and fire up more sustainable value-creating contributions. The QILT collection is dated, error-riddled, hardly spurs a policy murmur, and fails to ignite education or social change. Major education systems and big global companies are already delivering new solutions. Australia, once innovator, now lags. Australia needs to implement tomorrow’s solutions, most already validated and ready to go. 2050 starts today, as it takes two decades to bed-down major data collections. Let’s imagine and create!

Figure 2: Time to re-weave wilting QILT

Carving new ideas

What kind of information would spur university flourishing? There are good options, beyond incremental advances in existing collections. International research has revealed the need for more timely information on how universities, and the people within them, engage and work with communities. Current institutional data is largely transactional and inward looking. It does not reflect how universities are contributing to communities and adding social value. Institutional analyses have charted how digital and other transformations have blurred traditional boundaries between universities and communities. As higher education blurs into online and physical experiences for many more global participants, it is both a timely and necessary project to ascertain how to capture people’s engagement.

Figure 3: New information environment

This move involves shifting institutional emphasis on traditional ‘student experience’ to a much broader, more socially deliberative concept of ‘education value’. This view looks at how much larger and more integrated education institutions engage many more communities and learning arrangements. This is very different from looking at the engagement of admitted students within institutions, and only minor interactions with ‘outside’ communities. This shift envisages both looking at how students participate within prescribed frames and looking at how students and institutions engage in hybrid ways to co-create learning opportunities and credentials.

Novel analytical techniques and methods are available. Researchers and institutions keep evolving, innovating, and discovering important phenomena to measure. Platforms for collecting and using education information have evolved while system-level data in Australia has stagnated. The evolved platforms open new prospects for garnering relevant insights. Australia pioneered work in this field; now it lags innovation in North America, Europe, and Asia.

Information to drive education value

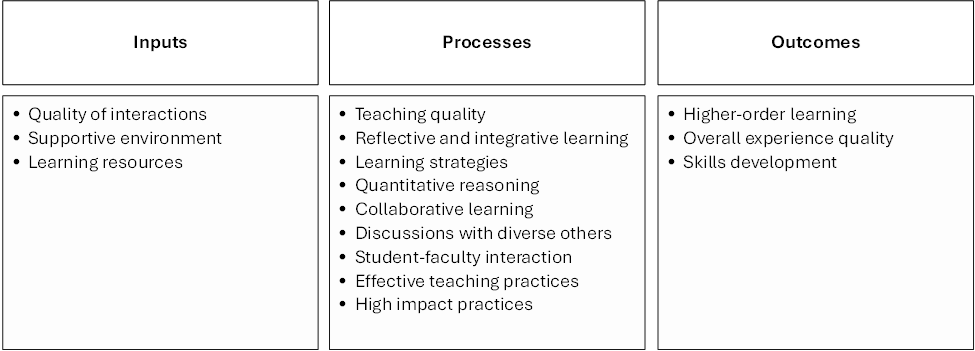

After two decades developing the student engagement agenda, the world has evidence about what has been achieved, and the limits of further progress. International research on student engagement spanning dozens of countries and years has highlighted several common measures of education inputs, processes and outcomes (Figure 4). Following the ‘internal logic’ etched decades ago, these measures focus on class and campus matters.

Figure 4: Prevailing student engagement measures

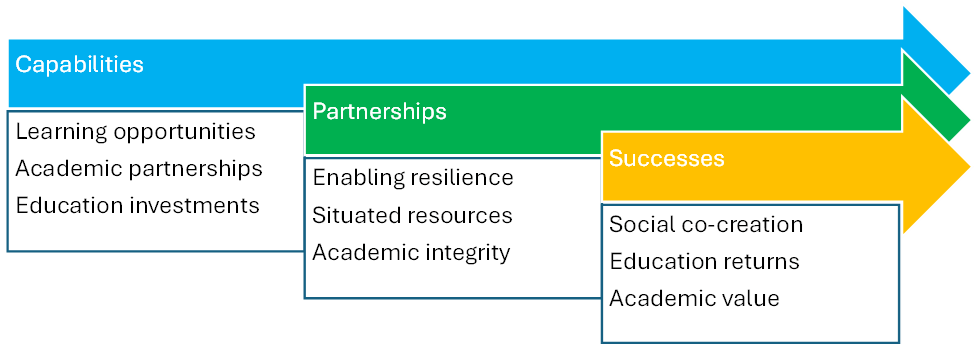

Synthesizing cross-national research has helped render nine topics that advance ‘education value’, and help universities and people engage in broader ways. We can articulate these topics in terms of three capabilities (inputs), three partnerships (processes), and three successes (outcomes) (Figure 5). These topics go well beyond the larger and more developed array of information developed over recent decades to measure ‘student satisfaction’, ‘student experience’ or ‘student engagement’ listed in Figure 4. These nine education value measures are unpacked below.

Figure 5: Education value indicators

First, ‘learning opportunities’.

- Do faculties, institutions, and systems deploy learner- or learning-centric, rather than structural, systems for opening learning opportunities to those who need them?

- Higher education markets are transforming. There is a need to match radically different forms of provision with much larger and more diverse learner markets. Highly batched or structured approaches to ‘admission’ are unlikely to suffice. Rather than ‘admit people to courses’, there is a present and pressing need to ‘link needs with resources’.

- Accordingly, an important indicator of education value surely boils down to whether platforms are in place which enable people and education to connect up and engage.

Second, an indicator of ‘academic partnerships’.

- Institutional infrastructure matters, though in unfolding and interesting ways. The volume of library books, ivy-coated buildings, plush endowments, and silver-coated research reputations are insufficient sources of value. Education experiences happen online. They can often be much more geographically and temporally distributed across places and learners’ lives. Digital partnerships and investments which higher education institutions make in this context matter a lot.

- A contemporary and growing facet of engagement is therefore the extent to which institutions have matured educational infrastructure with academic partnerships, invested in digital infrastructure, and built hybrid learning spaces.

Third, resources matter for institutions’ capability to furnish conditions that help students learn.

- Too few indicators of higher education quality or performance touch on institutional expenditure, partly due to the opaque nature of university costing provision of teaching across disciplines and units and partly due to complexities around generalizability.

- But realistically, resources cannot be ignored. In particular, the relative budget spent on education services, as opposed to research, works, or operations, affirms an institution’s investment in engaging students. Importantly, such information must be relativized to each institution. This information might be called ‘education investments’.

Fourth, helping, or supporting, people to learn is a critical facet of engagement.

- The United States suite of student engagement surveys put significant emphasis on support provided by institutions, faculty, support staff, peers, infrastructure, resources, and the broader environment. But what support meant in the 1990s is different to what it means today? Presumably what it means will differ over the next 20-plus years.

- Ultimately, however, what counts is the impact and learning outcome benefits rather than provision of support. Do institutions have the capability to understand and help each student where they are? How long does it take an institution to know if a student has missed a touchpoint or milestone? How long does it take them to deploy an effective response?

- These practical considerations require platforms and experts capable of implementing appropriate forms of information, analytics, diagnostics, and intervention. This might be termed ‘enabling resilience’.

Fifth, for too long, the system has used ‘curriculum’ indiscriminately to gesture towards university-level plans, faculty plans, course plans, and the ideas learners receive.

- As universities reformulate learning in many ways, ‘curriculum’ increasingly refers to ‘objects’, ‘resources’ and ‘parcels’. The reality is that learners build up knowledge using a tapestry of supplied and found objects. This situation requires institutions to frame learning experiences in engaging and contributing ways.

- Meaningful questions focus on whether institutions furnish curriculum accessible to non-traditional students, curriculum which can be co-created and which involves work, community, and world experiences. This phenomenon might be termed ‘situated resources’. It goes far beyond student engagement with curriculum.

Sixth, the world needs better information on teachers and teaching.

- Much of the focus and many specifics are a timeless testament to the enduring appeal of the ‘teachers and teaching’ perspective.

- Many existing surveys do rightly incorporate assumptions about academic work and teaching arrangements. Both have changed, and so must the questions used for evaluation. Looking into a future in which higher education institutions will employ dedicated teachers as opposed to teaching/research uber professors, it becomes meaningful to ask about the specific nature of teaching capabilities. Institutions need to get better at capturing and making use of the variety of experiences and achievements of their staff and using them to learners’ benefits.

- As well, academic integrity will play a more explicit role. Once upon a time, when a small number of global colleagues caught up to compare notes and standards, there was reasonable confidence in the integrity of teaching and learning.

- As higher education expands, and as threats diversify and multiply, ensuring quality requires increasing complexity and infrastructure. How many faculty are training and developed as teachers? To what extent do student-facing faculty engage in continuous professional development? How much time do teachers have to spend with students? How is academic integrity being sustained? What teaching innovations are institutions devising and implementing?

- Such concerns can be distilled into a rejuvenated concept of ‘academic integrity’.

Seventh, the extent to which higher education is conducted with and within communities.

- More and more education is integrated as one experience among many in people’s lives. The world is steering towards sustainability and myriad forms of co-contribution.

- Even prestigious pockets of higher education, which by definition are far from the ‘norm core’, rest more steadily and firmly on co-creation with and within a suite of communities. This turns the concept of ‘enrichment’ on its head. What matters most is whether the institution is reaching beyond its walls into the lives of a broader, potentially global, population.

- This is a step-change from the idea of students being ‘enriched’ within an institutional frame. Are institutions enriching their communities? Whether an institution and its community are engaging with sustainability goals might be relevant. This operating environment might be referred to as ‘social co-creation’.

Eighth, people engage with higher education to succeed.

- For most, this means getting a job or doing more higher value work. There are intrinsic knowledge and intellectual dividends, and of course broader socioeconomic returns for graduates and communities.

- Recent years have seen a proliferation of econometric indicators about graduate returns and returns on investment. Yes, information on jobs, work, and financial and practical returns matter.

- Yet ultimately, and profoundly, we must answer this question: is cogent information available to help stakeholders and participants alike understand the value higher education creates, and how best to engage in ways that extend that value? This context might be called ‘education returns’.

Ninth, higher education success is deeper than just getting a job. It goes beyond financial reward.

- How, and to what extent therefore, are learners and institutions engaging with multivalent forms of success? This is a reasonable question to ask of higher education, and to report to those seeking to engage.

- Do institutions and students even know what they are meant to achieve? Are institutions engaged in kinds of assessment validation and innovation required to assure success? Do institutions report generalisable measures of student success? This ecology of success might be termed ‘academic value’.

Tip-toeing ahead

These ideas offer the basis for promulgating a shift in conceptualizing and actualizing work on education value, moving to something broad in reach, something that touches on matters of sociology, governance and contexts shaping higher education.

This goes beyond work primarily rooted in learning and development. It embraces the politics and sociology of a future in which universities are no longer the ‘biggest kid on the block’. The broader reach of ideas needs to be expanded conceptually, debated, operationalized and validated. At scale, this takes three to five years, so it is time to start now. Care is required to ensure resulting information will help regulators, policymakers, institutions, teachers, students, and the broader public. Luckily, lots of data are lying in wait and ready to flesh out the nine articulated dimensions.

Monitoring all universities with the same indicators promotes a beige sameness, contrary to institutional individuation. Universities, like academics, must be encouraged to pursue disciplined and creative approaches to teaching and research. Core business must be delivered, and common data threads are important, but innovation is essential to rejuvenation and progress. This approach certainly does not involve throwing away the excellent foundations set by data designed in the 1980s and 2000s. Its influence is in adding to these foundations in contributing and impactful ways. Universities and higher education around the world have been hit by volatile and disruptive forces in recent years, testing resilience and endurance. Credible information on education and learning will play a major role in building knowledge, transforming skills and designing the shape of things to come. Generating new information on education is essential for the sustainability of universities and their contribution to local and global communities.

Further reading for inquiring minds

Sections of this briefing are drawn from: Coates, H., Gao, X., Guo, F. & Shi, J. (2022). Global Student Engagement: Policy insights and international research perspectives. London: Routledge.

Coates, H. & Matthews, K. (Eds.) (2018). Frontier perspectives and insights into higher education student success. Special Issue of Higher Education Research and Development, 37(5), 903-1094.

Coates, H. (2017a). The Market for Learning: Leading transparent higher education. Dordrecht: Springer.

Coates, H. (Ed.) (2017b). Productivity in Higher Education: Research insights for universities and governments in Asia. Tokyo: Asian Productivity Organisation.

Coates, H. (2018). Postsecondary Punters: Creating new platforms for higher education success. In: Weingarten, H., Hicks, M. & Kaufman, A. (Ed.) Beyond Enrolment: Measuring Academic Quality. Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Coates, H., Kelly, P. Naylor, R. & Borden, V. (2016). Innovative Approaches for Enhancing the 21st Century Student Experience. Alternation.

Hong, X., Liu, L. & Coates, H. (2021). Evaluating university social contribution: Insights and concepts from Chinese higher education. In: Tauginienė, L. & Pučėtaitė, R. (Eds.) Managing Social Responsibility in Universities: Organisational responses to sustainability. New YORK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Li, R. & Coates, H. (2020). Social service of higher education institutions: From ivory tower to engaged universities. Journal of Higher Education Management, 14(4), 96-106.

Richardson, S. & Coates, H. (2014). Essential foundations for establishing equivalence in cross-national higher education assessment. Higher Education, 68(6), 825-836.

Yang, J., Wang, C., Liu, L., Croucher, G., Moore, K. & Coates. H. (2020). The productivity of leading global universities: Empirical insights and implications for higher education. In: Broucker, B., Borden, V., Kallenberg, T. & Milsom, C. (Eds.) Responsibility of Higher Education Systems. What? How? Why? Leiden: Brill.