Blasting beyond dated logic to buoy community value

Executive brief

Universities have become too skinny, too reliant on and blinded by a small number of dated and aggregated metrics.

- Universities will flourish by proving the value they add to the communities which surround and sustain them.

- The world’s largest higher education systems are moving beyond narrow indicators relevant to only a small fraction of institutions.

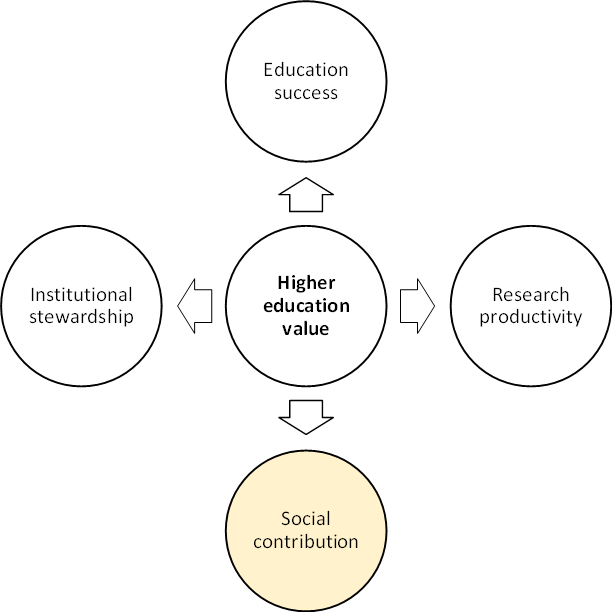

- To broaden engagement leaders must curate new metrics around institutional stewardship, education success, research productivity and social contribution.

Now’s the time to:

- Fatten up these wonderous institutions for a new era of broader contribution, and

- Make clear the vitality and significance of universities and their capacity to tackle huge problems.

Time for action! Universities must do and prove that they are excellent at partnering with society.

- Address declining trust and renewing a social license to operate.

- Work with governments and civil society to co-create solutions to thorny challenges around sustainability, peace, education and health.

- Need to reorient away from research reputations and embrace the communities which surround and sustain them.

- Need for new indicators and dialogue already being embraced by major education systems throughout the world.

Hamish Coates, Angel Calderon

Stargazing with feet on the ground

Everyone wants every university to be globally competitive, successful and locally relevant. This briefing looks at how many universities have chased stars during the ‘global era’. It shows how this has led many to wander aimlessly, with perhaps more than a few getting lost. Universities are progressively shifting gear from full globalization to meaningful regional and in place engagement. This briefing advances recommendations for rebooting for a ‘relevant future’. The ideas spring from research with major education systems which has yielded findings that are already being used to drive systemwide transformation.

A whole ‘global’ world has shaped up in recent decades, full of envy-inspiring luxury brands, national excellence initiatives, superstar scholars, and ‘world class’ rhetoric. In the 1990s, domestic consumer guides began to proliferate to inform prospective students about institutions and programs. These domestic ratings primed the sector for the emergence of more aspirational global rankings. The global era, launched by Chinese President Jiang Zemin in May 1998 at Peking University (the ‘Project 958’), stimulated university researchers and executives, invariably ambitious and competitive people. The opening and growth of world trade inspired governments to loosen policy levers and enable people and funds to flow between more porous national systems. In many countries, higher education was liberalized and opened to market forces. Top teachers piled up flier miles as their eloquence was sought around the world. Students thrived on the scents of diverse cultures, cuisines, and curricula. Perhaps most importantly, retail-friendly university lists filled an information void and opened higher education to new audiences. Universities have undeniably thrived.

Chasing global stars has been thrilling, but also miserable and alienating. It has also meant preferencing certain ambitions, investments and initiatives over others. Indeed, the pursuit of global excellence has generated dirty laundry, collateral damage and an abundance of failed endeavor. To captivate everyone’s imagination global rankings have reduced universities to a number, void of any meaningful narrative. The ‘world class logic’, unpacked below, has led even the most well-funded public universities to commercialize and digitally commoditize education programs. It has advantaged research fields which can be quickly and explicitly codified in bibliometric lists and related by-products. It has been fool’s gold, engaging university leaders and decision makers with no hope of being ‘number one’ in futile striving. Importantly, chasing global stars has led many institutions to lift their feet off the ground and neglect local and regional communities. Universities as critical pillars of society have lost space to show how they engage, connect and are a trusted community institutions.

It is time to step back, take a breath, and find ways to make universities, palpitate, be vibrant and more integral in their community. Universities do lots for local communities, though it is often complex, quiet and opaque. And they can always do more. Lately, universities have focused too much on ‘impact’, policy advocacy, and aiming to please market forces. All universities, even the most ‘global’ serve interests and needs which are much closer to home. Along with striving for global reputation, academics might be incentivized to contribute to local businesses and organizations. What logic, or way of thinking or talking, would inspire such broader forms of engagement? Before the obsession with performance measurement, universities reported how they were engaged and partnered with community, and what progress was made to make a difference. What metrics would incentivize relevant institutional behavior? This briefing provides tested options.

The intentions driving a striving to articulate broader contributions are clear. At the broadest level, enhancing engagement seeks to ensure that contemporary and future university governance, management and stewardship processes support effective social engagement. Progress in this area should ensure that universities are accessible, outward reaching and responsive to communities. It should increase the social, environmental, and economic value of lifelong learning and research to the benefit of university communities. Aligning and situating academic endeavors with social contexts should help design and deliver high quality teaching, learning and research which responds to social needs. Designing indicators to collect data from multiple regions or multiple universities should inform monitoring, improvement, and enhancement. Over recent decades, several attempts have been made but these have been shelved as being too complex and resource intensive. This is no longer the case.

Disrupting the dominating logic

Major thinking and development is taking place around universities’ environmental sustainability, economic and social impact. While research on the social engagement of universities is in its infancy, it is increasingly popular and propelled by the quest for new relevance. Recent international scans have revealed that this is an eclectic field, and while various platforms have proliferated none have moved into the mainstream. As higher education shifts into new futures, big interest narrows around how to understand hence boost the ‘value’ created and contributed to a diverse range of communities. What ideas, stories, forms of evaluation, information and data can shape transformation and growth? How to build on existing foundations, and carve new tracks?

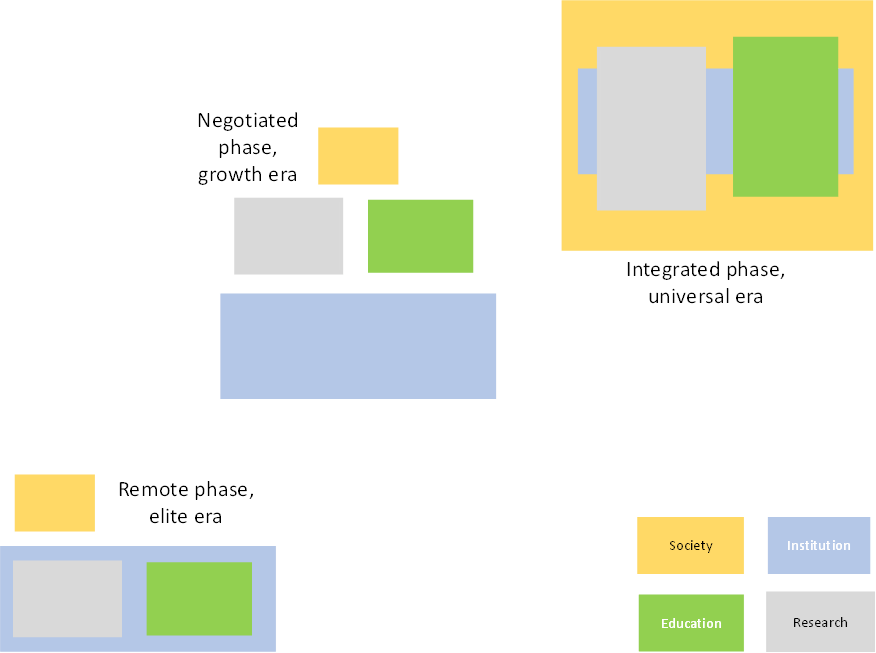

This briefing reports outcomes from evaluation design research conducted to make sector-wide sense and use of this large, eclectic, and especially important field. This work was underpinned by the re-analysis of two dominant assumptions reshaping contemporary higher education. First, it was assumed that the ‘social dimension’ has grown beyond a remote or negotiated ‘vertical’ and is instead playing an integrated role in reshaping the core. As Figure 1 depicts, in what is often referred to as an ‘elite’, ‘prestigious’ or ‘colonial’ era, universities were separated from society through selective admissions, protected knowledge, and physical campus walls. During the recent global growth era, universities negotiated various points of social engagement around specific programs, campuses and projects. Universities’ agreements with government were loose on engagement with community. Being relevant in a ‘globally connected and locally relevant’ universal era requires a much more integrated perspective in which community is a grounding rather than consequence of academic work.

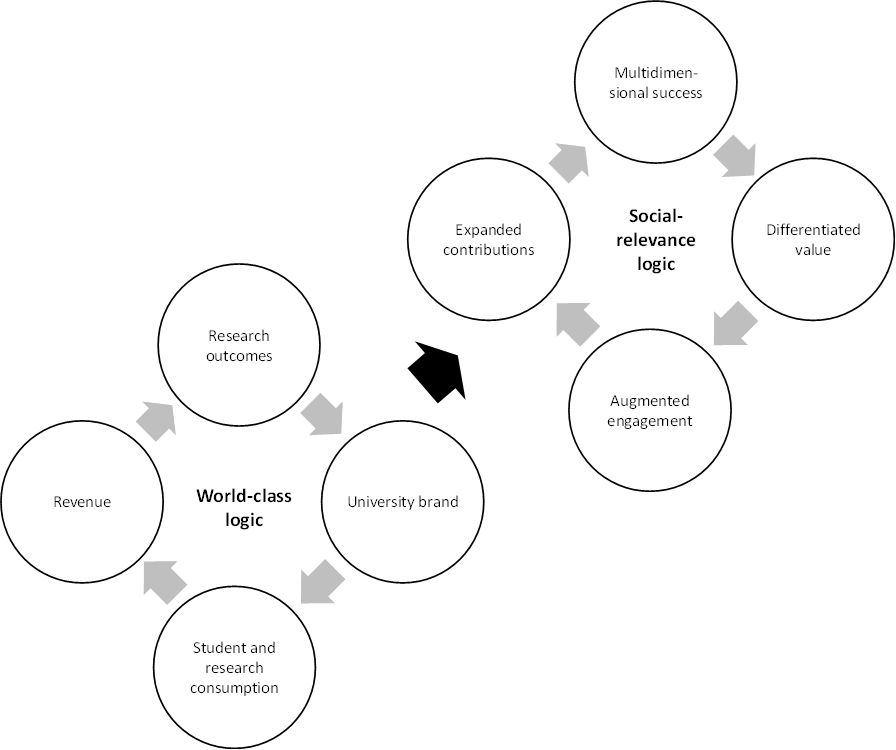

Second, it was deduced that the strategic flow which has grown to undergird and shape higher education in the recent global growth era needs to change. Shifting to an integrated or universal space sparks new academic and institutional assumptions Figure 2 depicts the under the ‘world-class logic’, globally striving universities parlay tuition revenue into research and specifically publication outcomes to inflate the university brand to stimulate consumption and growth. Universities have become too obsessed with the notion of measuring research outputs. Community connection and engagement have taken a backseat. According to a ‘social-relevance logic’, already being implemented at scale in various systems, universities create value on many fronts, parlay this into many forms of augmented engagement, expand their scope and scale of their contributions, and generate multidimensional successes. This broader view embraces accomplishments in advancing the workforce and tackling government and industry challenges.

Curating new perspectives

New language and information are needed to represent university performance in socially relevant dimensions. Reliance on bibliometric measurement must lessen. Higher education needs to get back to basics and capture imagination about how universities can make a difference in society. Universities need to make the third mission the key pillar in going forward. There remains a pressing need for information that helps institutions and people discover how to best engage, create, and contribute with higher education. What sort of information is likely to impel future higher education leaders to reach beyond prevailing arrangements and create socially relevant value?

The evolution of universities and digital platforms during the global era has yielded technical insight. Information must focus on university outcomes and processes as much as inputs like funding and admissions. Echoing shifts underway in other sectors, it must give insight into pathways for impact and value. As well, information must focus on individuals as well as institutions and systems. It must go beyond university research activities to consider other core facets of academic work, notably education, but also broader socioeconomic forms of engagement, how universities are agents of change and making good use of their social license. The information must be dynamically shaped by clever algorithms rather than presented as static ordinal lists. Such information should frame novel and larger kinds of university contribution and responsibility. The information should resonate with and compel university leaders to marry competing academic (education and research) with external (societal, commercial and political) imperatives. Unless indicators entice universities to step ahead, they fail to capture the imagination of leaders and spur governance and management improvements. Faculty, not just university or policy leaders, must be inspired and engaged to change how things get done and showcase how their stewardship initiatives benefit the community. Ideally, data on social engagement should be immediately useful to help people do better in their work. Often this information is not captured or easily retrieved due to internal processes and barriers hindering its usability. Any disclosures about higher education must first and foremost be relevant to the public and taxpayer, particularly people who know little about universities, and particularly when it concerns how they can engage. Information that is collected about what an institution is and does provides legitimacy to the purpose and mission of universities, and to the set of legal instruments that fund, regulate, quality assure and assess performance.

Designing worthwhile information

Recent large-scale evaluation design built an architecture to advance these ideas. The architecture in Figure 3 spotlights four dimensions. The dimensions are designed to be of immediate relevance to system policy (i.e., legitimacy and ideological context), institutional leadership (i.e., relevance), academic practice (i.e., enablers), and consumer interests (i.e., transparency). They go well beyond institution-level preoccupations with research scores to provide additional insights into fields of interest to many people. Emphasizing these areas is needed to shift into the integrated and socially relevant phase.

Education success is the core of most of the world’s higher education institutions. Research has clarified that any useful architecture should embrace education success in terms of student admissions, engagement, and learning outcomes, and graduate destinations and career progression. Foundation work has been laid in these areas over the last decade, furnishing necessary data and technology. Such work has not yielded perfect solutions, but it is arguably far more advanced than were bibliometrics when they were commercialized into global rankings. As has been evident in the rise of bibliometric science over the last three decades, resting system and institution growth expectations on indicators will ensure rapid technical development. Education is too important to ignore and let wane.

Research productivity comprises faculty output, research quality and academic impact. To date, research rankings have exploited bibliometric data to emphasize the volume and peer-recognition of a researcher’s or department’s output. While ready to hand, these measures fail to say anything about the broader contribution of research. To frame future practice, it is essential to add more advanced metrics relating to engagement and pathways for impact. These metrics cover conventional products derived directly from research like publications, patents and doctoral enrolments and completions, but also step beyond to examine links with industry, public impact, and the creation of shared value. In recent years, there has been increased emphasis on measuring universities’ progress towards achieving the sustainable development agenda and policy impact. New data on research has the capacity to stimulate new kinds of socially relevant research, beyond prevailing reductionist approaches.

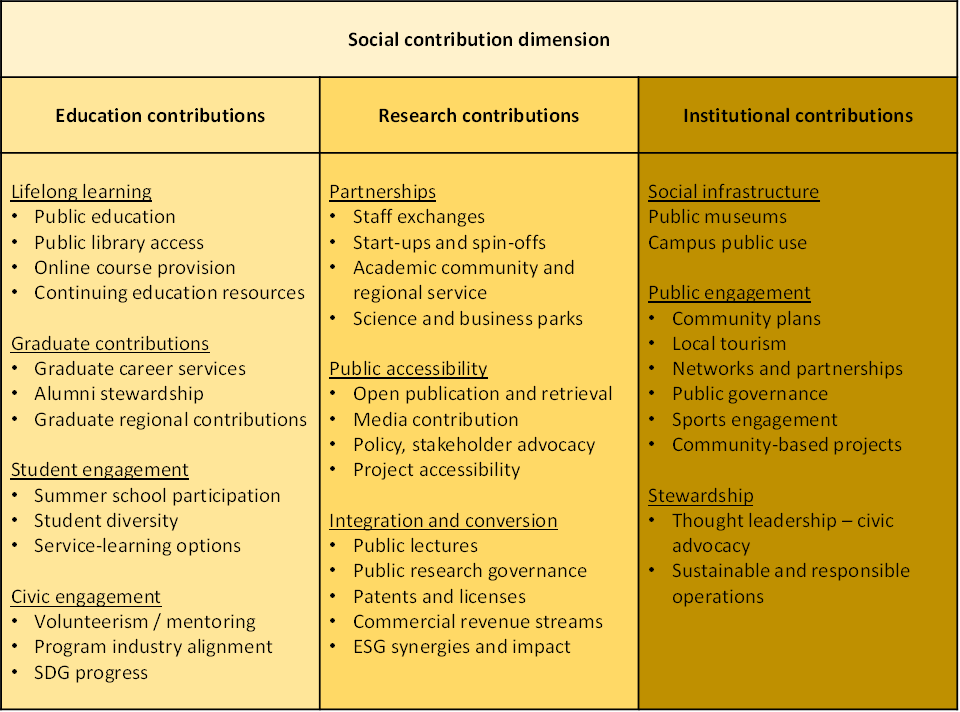

Social contribution can be viewed as spanning regional engagement, national development, and international impact. The scope of such engagement is of course shaped by the mission, scale of the university and locations in which it operates and serves. In general terms social contribution may be organized into forms of engagement that stem from leading education and research, operations and governance. For instance:

- Education-related forms of engagement might include the extent of open courseware, the provision of community-based education, and the contribution of graduates and alumni;

- Research contributions can take account of the scope and scale of projects and start-ups, staff exchanges, engagement via media and lectures, and more traditional academic service contributions;

- Institution-related contributions might take account of a university’s networks and partnerships (within and across jurisdictions), the public use of facilities, and even the provision of strategic plans and budgets for such engagement; and

- University’s stewardship and outreach initiatives focused on environmental sustainability and partnering with civic society to progress the sustainable development agenda.

To measure these facets of social influence, the architecture can be designed to integrate developments in corporate governance and social impact assessment to chart new ways for understanding and creating the social engagement of universities and disciplinary fields. This means touching on techniques related to organizational social responsibility, university-industry relations, and the links between fields and the industries and professions that they represent. Much of the technical and practical efforts required in this area involve bringing universities into broader alignment with the way other major sectors report their social influence.

Figure 4 delves deeper into the social contribution dimension, shortlisting feasible indicators. In this articulation, the social value of education is construed not just by the number of students admitted, retained, and graduated. The value of research is much more than publications and about the relevance and contribution. Institutional forms of engagement go to the way in which universities partner and embrace relevant communities. Spurred by the need for national and public relevance, this work is building fast in Asia and Europe. This is a young field and there is some way to go to build and deliver mature indicators. Development work will need to confront very divergent stakeholder perspectives, the blossoming of frameworks, the challenges of context, and the need for grounding in concrete institutional life.

Institutional stewardship is an important facet of any reporting system which helps higher education institutions develop. Institution growth is about governance and leadership, management effectiveness, and the creation of distinctive value. Top-ranked ‘world-class’ universities comprise a tiny one per cent of all institutions, and all universities must be engaged to become excellent in their own distinctive ways. To encourage this, indicator systems must provide scope for each university to define and demonstrate their own unique excellence. To enable this, indicator architectures must draw on proven and innovative managerial and actuarial perspectives about how to understand and advance the success/productivity of higher education institutions. Emerging policy-level research across Asia has proven the feasibility of collecting and compiling such data. It should define ways to reflect productivity that matter to all universities, which enable distinctive expressions aligned with strategy.

Fattening universities for society

This broad dimensional architecture paves the need and foundations for designing indicators which really define and establish the social characteristics of future universities. This is a complex task, not least because everyone sees this matter as important, which has led to wild proliferation of frameworks, indicators, data suggestions, and reports. These frameworks furnish different perspectives, bring out the complexities of drawing tight boundaries around inherently complex academic work, reveal that much prior work has had gained little traction, and revealed the need to identify social characteristics which are internationally generalizable. There is a pressing need to advance major research in this field, and move beyond the hesitation of taking the first steps in this endeavor.

The four dimensions in Figure 3 cover what is conventionally identified as the primary academic functions. Each adds its own value and is appropriately general to cover relevant information needs. For instance, excellent research and education can go together, but they often do not, and any assumption that great research implies education success is easy to prove false. Likewise, being managed well does not necessitate that a university is socially influential. Ultimately, links between these four dimensions and relevant underpinning metrics are contingent and shaped by a range of contexts and interests. This implies the need for a dynamic reporting platform that enables end users to shape what they seek to discover. Continuing to rely on static and highly aggregated research metrics will not unlock the new value sought for future higher education.

Of course, the real-world creation of innovation on this scale does not flow without obstacles. Self-evidently, the established international rankings, technology and management consultancy firms are supported by power dynamics which greatly underpin reputation and prestige. Many of the particularly prominent earlier generation reporting initiatives have also secured a first-mover advantage through being early entrants in a young field. The lack of courage and perceived need for reform is a hazard, particularly among powerful interests with stakes in the status quo, though the global tectonic forces sketched at the outset of this paper seem to be swinging with a forward momentum. Indicator definition and data collection has proved troublesome and costly, particularly in relation to education and engagement work. Over the past twenty years, universities have become less interested in benchmarking and have relied too much on high-level measurement, rather than understanding and assessing the economic, environmental, social and cultural impact of higher education on a particular geographical location. Establishing that data is robust on a large scale is always challenging, but there is substantial room to align techniques in this field with expected standards in broader education cross-national assessment studies. Clearly, development will be patterned by a range of forces.

Higher education needs to move a long way to touch, embrace and progress in positive ways. As the ‘integrated socially relevant logic’ conveys, this cannot happen with higher education alone. First, it is necessary to unshackle universities from current operating environments which have come to threaten system and institutional growth. Environmental mechanisms built up over the last few decades are yielding diminishing returns. It is time to open space and options for creative development, imagining different futures. Doing this makes it possible to define perspectives helpful for paving alternative value indicators. Tracing implications of these activities is helpful for spurring entrepreneurial transformations.

Further reading for inquiring minds

Sections of this briefing are drawn from: Hong, X., Liu, L., Bice, S. & Coates, H. (2021). Evaluating university social contribution: Insights and concepts from Chinese higher education. In: Tauginienė, L. & Pučėtaitė, R. (Eds.) Managing Social Responsibility in Universities: Organisational responses to sustainability. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Bice, S. & Coates, H. (2016). University sustainability reporting: Taking stock of transparency. Tertiary Education and Management, 22(1), 1-18.

Bice, S., Nealy, K. & Einfeld, C. (2019). Next generation engagement: Setting a research agenda for community engagement in Australia’s infrastructure sector. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 78(2), 290–310.

Cantwell, B. Coates, H. & King, R. (Eds.) (2018). Handbook on the Politics of Higher Education. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Chung, E. & Coates, H. (2016). A journey to measure student community engagement benefits: Evidence from Australia. International Journal of Service Management and Sustainability, 3(1), 30-53.

Coates, H. (2007). Excellent Measures Precede Measures of Excellence. Higher Education Policy and Management, 29(1), 87-94.

Coates, H. (2017). The Market for Learning: Leading transparent higher education. Dordrecht: Springer.

Coates, H. (2020). Higher Education Design: Big deal partnerships, technologies and capabilities. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan.

Coates, H. (Ed.) (2017). Productivity in Higher Education: Research insights for universities and governments in Asia. Tokyo: Asian Productivity Organisation.

Coates, H., Gao, X., Guo, F. & Shi, J. (2022). Global Student Engagement: Policy insights and international research perspectives. London: Routledge.

Coates, H., Weerakkody, U., Jerez, E., Wells, M. & Popenici, S. (2018). Transparency is the lynchpin for higher education success. In: Cantwell, B. Coates, H. & King, R. (Eds.) Handbook on the Politics of Higher Education. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Garlick, S. & Langworthy, A. (2008). Benchmarking University Community Engagement: Developing a national approach in Australia. Higher Education Management and Policy, 20/2.

Guo, F., Luo, Y, Liu, L., Shi, J. & Coates, H. (2019). Analysing mechanisms for evaluating higher education outcomes in China. Higher Education Policy, 32, 557-575.

Hazelkorn, E., Coates, H. & McCormick, A. (Eds.) (2018). Research Handbook on Quality, Performance and Accountability in Higher Education. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Hong, X., Calderon, A. & Coates, J. (2023). Universities and SDGs: Evidence of engagement and contributions, and pathways for development. Policy Reviews in Higher Education, 7(1), 56-77.

Jongbloed, B. & Benneworth, P. (2013). Learning from history: Previous attempts to measure universities’ community impacts. In: P. Benneworth (Ed.), University Engagement with Socially Excluded Communities. Dordrecht: Springer.

Kulkarni, A., Calderon, A. & Douglas, A. (2015). Toward a knowledge Footprint framework: Initial baby steps. In: Institutional Research and Planning in Higher Education. Singapore: Routledge.

Li, R. & Coates, H. (2020). Social service of higher education institutions: From ivory tower to engaged universities. Journal of Higher Education Management, 14(4), 96-106.

Liu L., Hong, X. Li, R. & Coates. H. (2020). On the evaluation of university’s contribution to society: The practice and enlightenment from America, Australia and Japan. Tsinghua Journal of Education, 41(1), 134-141.

Liu, L. & Coates, H. (2019). Enlightenment of European governance reform on China’s Double First-Class Construction Project. Higher Education Exploration.